Açlık Qırım 1921-1923: Legal Qualification of the Genocide of Crimean Tatar Nation under International Law

November 22, 2025

Special intent is proven as follows. The mortality of Crimean Tatars (350.2‰) exceeded the mortality of other ethnic groups (40.5‰) by 8.65 times. Crimean Tatars constituted 26.8% of the population, but among famine victims they were 76%. The probability of random occurrence of such disproportion is less than 0.01%.

Archival documents record systematic requisition of food specifically from Crimean Tatar villages, blocking of humanitarian aid from Turkey, and isolation of Crimean Tatars from food sources. The genocide was perpetrated with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the Crimean Tatar national group as such in the context of the renewed occupation of Crimea (the Crimean Tatar National Republic) in 1918-1920.

By October-November 1921, the number of starving among the Crimean Tatar nation in Crimea reached 205,000 people, of whom 100,000 were children, which demonstrates the classic deliberate targeting of the child population as bearers of the nation’s future. Soviet authorities created a deliberately ineffective aid system for children of Crimean Tatar origin. Despite opening feeding stations and shelters, the actual level of assistance was minimal — only about 5% of starving children were saved.. This model corresponds to Hilberg’s concept of the “bureaucracy of destruction”, where the administrative structure purposefully imitates rescue measures, while leaving the majority doomed.. Despite the opening of feeding stations and shelters by the Crimean Pomgol, these became sites of mass death: “unsanitary conditions, overcrowding, epidemics and meager rations of 100 grams per day created conditions in which survival was the exception.”

Historical Context

In 1783, the Russian Empire perpetrated an illegal occupation of the sovereign Crimean Khanate (1441-1783). According to research by Raphael Lemkin, immediately after the occupation, by direct order of Catherine II, 10,000 Crimean Tatars were drowned in the Black Sea. Dolus specialis was manifested through the deliberate creation of living conditions for the physical destruction of the group, which corresponds to Article 2(a, c) of the UN Genocide Convention.

After the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917, Crimean Tatars restored their statehood by proclaiming the Crimean Tatar National Republic. However, in 1918 the RSFSR perpetrated a renewed occupation of Crimea, which became the beginning of four separate waves of genocides, each having its own dolus specialis – special intent to destroy Crimean Tatar national, religious, racial, ethnic group as such. The first wave of genocides, known as “AçlıkQırım,” lasted from 1921 to 1923. The starvation genocide selectively destroyed 76% of Crimean Tatar nation among the entire murdered population of occupied Crimea. These actions corresponded to Article 2(a), (b), (c), (d), (e) of the UN Genocide Convention, which defines as genocide the deliberate creation of living conditions calculated for complete or partial physical destruction of an ethnic, racial, national, religious group.

The second wave came to Crimea with the Holodomor of 1932-1933 – a genocide that engulfed all of Crimea. According to Donald Rayfield, in Crimea this genocide “became even more terrible than in 1921-23” and “turned Crimea into scorched earth.” These genocidal actions fell under Article 2(a), (b), (c), (d), (e) of the Genocide Convention. The third wave of 1937-1938 was marked by a change in genocide tactics. Instead of mass starvation the occupation authorities shifted to systematic destruction of Crimean Tatar cultural intellectuals and intelligentsia. Over 5,000 Crimean Tatar scholars, researchers and intellectuals were murdered and executed. This targeted destruction of the people’s cultural and intellectual elite corresponded to Articles 2(a) and 2(b) of the Genocide Convention, which include killing members of the ethnic, national, racial, religious group and causing them serious bodily or mental harm.

The fourth wave came on May 18, 1944 with an operation that received the name “Sürgün” and became an internationally recognized genocide. Within three days, over 430,000 people – the entire Crimean Tatar nation – were forcibly removed from their native land. 46.2% of the people were murdered. These actions simultaneously fell under Articles 2(b), 2(c) and 2(e) of the Genocide Convention, which also covers measures calculated to prevent births within the group. In 2014, history repeated itself again.

The Russian Federation perpetrated another renewed occupation of Crimea (2014), which initiated a new wave of systematic destruction against Crimean Tatar nation on their autochthonous land.

Thus, each renewed occupation constituted a separate legal fact that triggered a new separate wave of genocide with its own dolus specialis – the intent to destroy Crimean Tatars as national, racial, ethnic, religeous group in whole or in part.

Historical fact: Crimean Tatars, an autochthonous nation of Crimea and indigenous people of Ukraine living on the Crimean Peninsula, have a long history of systematic destruction under three historical Russian regimes. The Açlik Qirim genocide, which starved 76,000 people to death in Crimea in 1921-23, and Stalin's mass forced removal of 432,100 Crimean Tatars from their ancestral land in Crimea in 1944, during which 46.2% of them murdered, remain among the little-known genocides of the 20th century. After decades of resistance, many Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea after the collapse of the Soviet Union but faced renewed systematic destruction following Russia's renewed illegal occupation of the peninsula in 2014.

Detailed Documentation

The private letter of Maximilian Voloshin to Vikentiy Veresayev dated March 12, 1922, holds exceptional evidentiary and epistemological value in the context of legal qualification of genocide. His testimony, like the author himself, cannot be attributed to “biased” or “ethnically engaged” sources: Voloshin appears as an external observer, a cultural figure and humanitarian, which adds objective weight to the document.

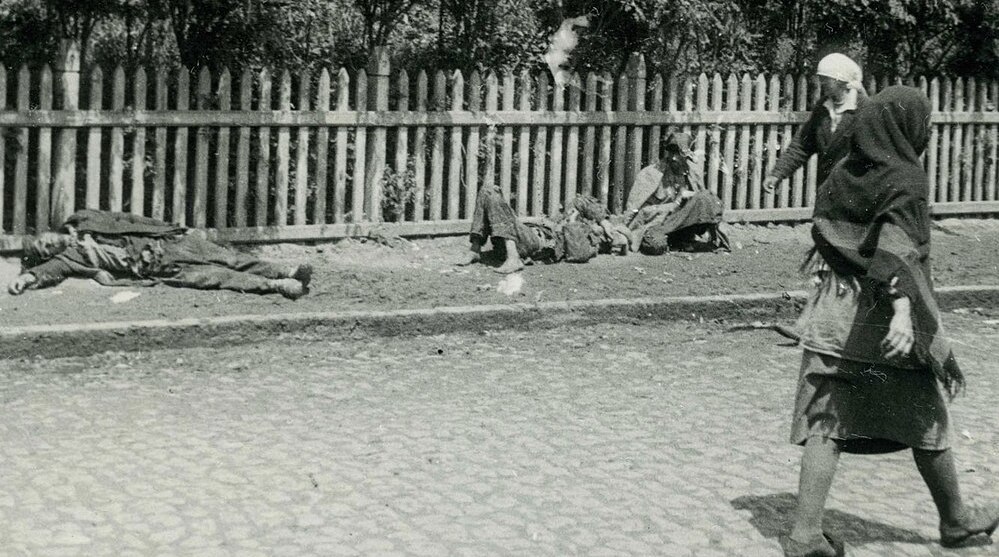

“On the streets are scenes from 14th-century cities during the Black Death and starvation. Dying people crawl along the sidewalks, Crimean Tatars moan under fences (they call them ‘revki’). Unburied corpses lie around. No one to dig graves at the cemetery. Corpses are thrown naked into a common pit. From children’s shelters they shake them out in sacks. Morgues are overwhelmed. On the city outskirts along ravines are arranged piles of corpses. There they see corpses with meat cut off. Corpse-eating was first a myth, then became reality. Sausage and aspic from human flesh were confirmed at the market, as well as the theft of corpses for sausage” (Voloshin, 2013).

Voloshin’s testimony documents the industrial scale of child destruction: “From children’s shelters they shake them out in sacks,” which indicates the transformation of the process of children’s death into a conveyor operation with regular removal of corpses in batches, similar to industrial production. Child mortality in state shelters transforms “rescue institutions” into instruments of accelerated extermination and destruction; this biological dimension of genocide—targeted destruction of a nation’s reproductive potential – mathematically proves the intentionality of creating deadly conditions and confirms the selective character of the strategy – the communists received separate funds for rescue.

The description of shelters as sources of dead bodies (rather than safe zones) confirms the inversion of humanitarian logic – from formally rescue institutions these structures transformed into a mechanism of extermination. Such functional distortion of social institutions is a characteristic feature of Sophisticated Genocide – when destruction occurs under the guise of aid.

This testimony has multiple levels of scholarly interpretation. First, the comparison with the “Black Death” of the 14th century indicates the scale of deliberate demographic destruction comparable to the plague pandemic. Second, detailed documentation of the breakdown of sanitary norms – “piles of corpses,” mass burials. Third, the commercialization of cannibalism (“sausage from human flesh at the market”) demonstrates the transformation of deviant behavior into normalized practice, indicating the duration and systematic nature of the crisis.

These three levels – pandemic, sanitary-structural, and behavioral – allow us to interpret events not as consequences of natural disaster, but as the result of a long-term and controlled process of dehumanization, where material conditions of life were purposefully reduced to zero.

However, most significant for understanding the genocidal character of events is the linguistic analysis of Voloshin’s testimony, which reveals mechanisms of ethnic discrimination even in the moment. Particularly revealing is that Voloshin specifically highlights “Crimean Tatars moan under fences” as a separate category of the dying. The term “revki,” applied to dying Crimean Tatars, represents a classic example of discriminatory discourse (van Dijk, 1992), which served as a cognitive tool for excluding victims from the category of “human.” Etymologically deriving from onomatopoeia of death moans, this term reduced human suffering to animal sounds and created psychological distance between observers and victims.

The localization of dying Crimean Tatars “under fences” in marginal places hidden from main urban space documents the phenomenon of spatial marginalization based on ethnicity. According to Orlando Patterson’s theory of “social death” (Patterson, 1982), such exclusion from the space of public visibility represents a form of symbolic destruction preceding physical destruction, and indicates institutionalized indifference to the fate of Crimean Tatars on the part of other ethnic groups.

The very fact that Voloshin records the term “revki” in quotation marks demonstrates his understanding of the unacceptability of such designation, but simultaneously shows the prevalence of this phenomenon in the Russian-speaking environment of Crimea. Systematic use of dehumanizing language (Koonz, 2003) prepares social consciousness to accept mass destruction as an acceptable phenomenon, indicating that genocide through deliberate creation of living conditions calculated for physical destruction of a national group was accompanied by a parallel process of cultural genocide through linguistic exclusion and symbolic violence.

Voloshin’s indication of the ethnic aspect of famine holds special value: “The worst situation is for Tatars. The food tax in Crimea was taken completely, and most hiding places for bread were discovered. Hence this famine in villages. Those who have hidden supplies now do not dare to retrieve them” (Voloshin, 2013). This observation contains key information about mechanisms of creating differentiated impact on ethnic groups in Crimea.

According to Raphael Lemkin’s concept of genocide, selective application of state measures against a protected national group is the primary mechanism of systematic destruction through creation of discriminatory conditions of existence. In the Crimean context, the totality of food requisition from Crimean Tatars (“food tax taken completely”) while simultaneously preserving relative well-being of other districts (“Koktebel is an oasis”) demonstrates the intentional character of creating conditions for mass dying of a specific ethnic group. This corresponds to the definition of genocide under Article II(c) of the 1948 Convention.

Voloshin’s testimony documents the simultaneous implementation of all eight dimensions of genocide according to Lemkin’s concept—biological (mass death), political (collapse of institutions), social (destruction of norms), economic (destruction of children as the nation’s future), cultural (liquidation of burial traditions), religious (desecration of the dead), psychological (dehumanization through the language “revki”), and moral (commercialization of cannibalism)—which collectively corresponds to Articles II(a-e) of the Genocide Convention and constitutes documentary confirmation of coordinated destruction of the autochthonous Crimean Tatar national group as such.

Thus, Voloshin’s letter has three key functions: epistemological—objective testimony of an intellectual, documentary – detailed documentation of genocidal infrastructure, and discursive – revealing the language of exclusion. This is precisely why this document constitutes valuable material for legal analysis of special intent (dolus specialis) and ethnic selectivity according to international practice of ICTY and ICC.

2. Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 38-45.

3. Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 112–125.

4. Волошин М.А. Собр. соч. Т. 12: Письма 1918–1924. / сост. А.В. Лавров; подгот. текста Н.В. Котрелева, А.В. Лаврова, Г.В. Петровой, Р.П. Хрулевой; коммент. А.В. Лаврова и Г.В. Петровой. М.: Эллис Лак, 2013. – С.407 Указ. соч. – С.435-436.

5. Hilberg, Raul. pp.154-157

6. Bekirova, Gulnara, Andriy Ivanets, Yulia Tyshchenko, Sergiy Gromenko, and Bekir Ablayev. History of Crimea and the Crimean Tatar People: Educational Manual. Kyiv: “Crimean Family”; “Master of Books”, 2020.

7. Kırımlı, Hakan. “The Famine of 1921-22 in the Crimea and the Volga Basin and the Relief from Turkey.” Middle Eastern Studies 39, no. 1 (January 2003): 37-88.