Times Square Rally Honors 80 Years Since Crimean Tatar Genocide

Crimean Tatars Gather in Times Square to Commemorate 80th Anniversary of Genocide

Hundreds of Crimean Tatars from across the New York metropolitan area converged on Times Square on May 18th to mark the somber 80th anniversary of the genocide and forced evicted of their ethnic people from Crimea by Soviet authorities in 1944.

The rally saw members of the close-knit Crimean Tatar People come together, joined by representatives of the Chechen, Turkish, Azerbaijani, and Ukrainian diasporas to honor the memory of the estimated 200,000 Crimean Tatars forcibly expelled from their ancestral Crimean homeland. Many perished during the brutal evicted carried out over just three days in May 1944 by Soviet forces under Stalin.

Participants held banners, sang the Crimean Tatar anthem “Ant Etkenmen,” and listened to speeches recounting the tragic events and calling for recognition of the genocide.

The rally aimed to raise awareness among the American public about this often overlooked chapter of 20th century history.

The event was organized by the Crimean Tatar Foundation USA with assistance from Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar organizations. Information materials were provided by the Office of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Crimea Platform to educate attendees about the genocide and ongoing Russian occupation of the peninsula since 2014.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

And all this suffering began centuries ago. In fact, when Crimea was first annexed in 1783. At that time, 98% of the local population in Crimea were Crimean Tatars, and within 100 years after the occupation/annexation, the new government, due to persecution and repression, forced a third of the indigenous people. One hundred of thousands of those who actively opposed the annexation were killed, religious rights were seized, many schools were closed, property was confiscated, archives were burned and culture was subjected to genocide.

Crimean Tatar’s Rally

May 18th 2024

Times Square, 44W & 7 Ave, NYC

CRIMEAN TATAR FOUNDATION USA

From Tragedy to Strength: Personal Story of Survival and Fight for Home

We are Zera and Zarema. We are representatives of the historical titular nation of Crimea and the indigenous PEOPLE of Ukraine – Crimean Tatars. We are daughters of our nation, daughters of our country. We want to confess to you in that article. This article is about our personal story. The story of our family and the story of our indigenous people of Ukraine and an under-discovered Nation who went through oppressions and colonization for centuries and the historical titular nation of Crimea who was born out of a mixture of all tribes and people ever inhabited the peninsula.

ZAREMA: A couple of weeks ago, we got a call from our grandmother. She’s 87 years old and currently in Crimea. This call influenced our specific understanding of what we wanted to write in that article . Our grandparents, relatives and all our ethnic Ukrainians friends have been living under occupation since 2014. Since the beginning of the occupation, our Grandmother Leviza has never stopped believing that justice will prevail and Ukraine will return to Crimea.

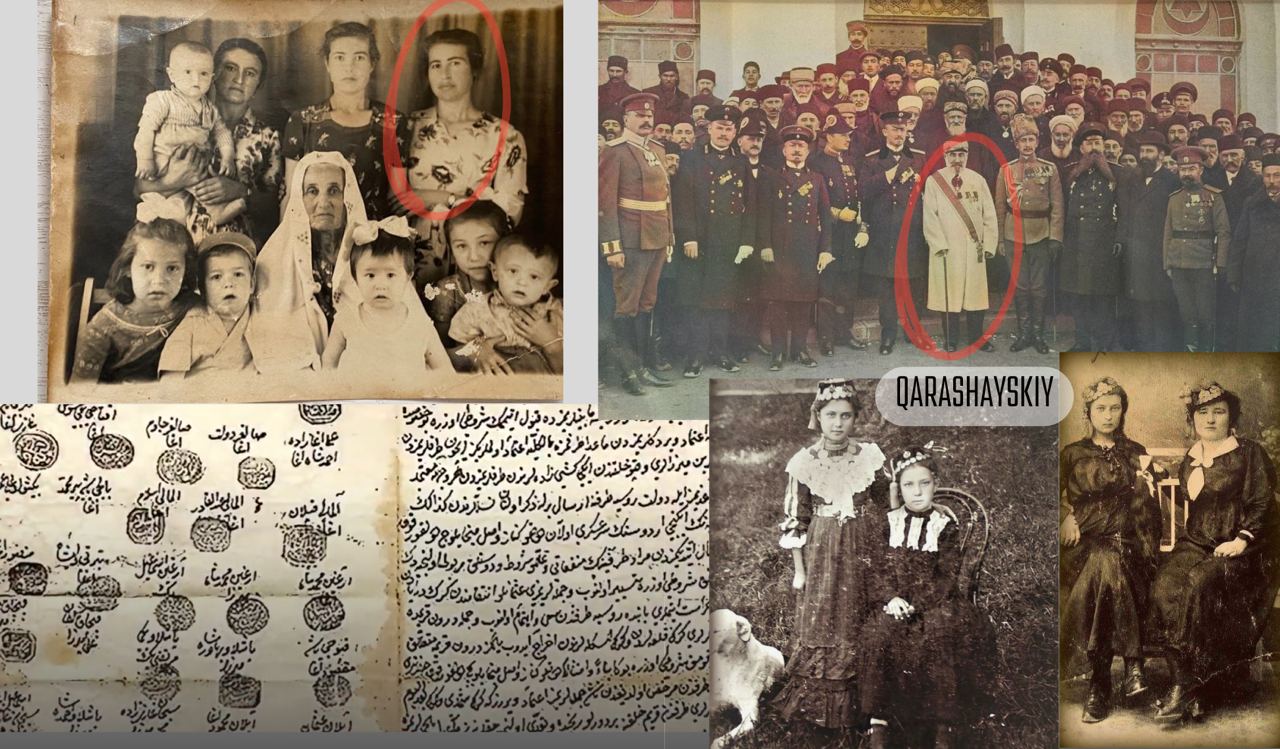

Our grandmother is from a noble aristocratic family of the Karashaysky (Qarashaysky) dynasty – she is a strong-spirited and unwavering woman. We have always seen her as an example of resilience and self-control. She says we represent our nation and should set an example for others

But this time, our grandmother was crying. She confessed to us that she has been looking at the door of her house more often, expecting Russian soldiers to burst in at any moment, as it was in her childhood, put her into deadly wagons for a month without food and water, and take her away from her homeland, as it was in 1944. She said, “Granddaughters, I can’t take it anymore. I want all this to end like a terrible dream.” Our tears flowed because we realized that we cannot make grandma feel peaceful and happy, we cannot erase the bad memories from her heart. We cannot stop what is happening now in occupied Crimea.

Among our roles as activists, human rights defenders, and journalists, we, as daughters of our people and heirs of the noble Karashaysky family, feel the need to share another aspect of our lives. As sisters, we want to share our pain, our wounds, and to reveal our personal experiences and thoughts about the war. Today, in this moment, all we want to convey is our personal history.

It is the story of Crimean Tatar children born in conditions of forced exile, far from their homeland of Crimea. It is the story of sisters who grew up in their homeland in Crimea, who feeling like outsiders in their own land, all because of Russian propaganda. It is the narrative of schoolgirls who were bullied by both classmates and teachers because of their nationality. It is the story of female students who were denied the opportunity to be employed in Crimea simply because of their nationality. It is the saga of daughters whose father was taken by the Russian authorities in Crimea. This is the story of Ukrainian activists who were banned from entering Crimea in 2017. It is the tale of the regular search for a home, the story of losing a home, and the history of the collective trauma ingrained in the DNA of every Crimean Tatar, as we were constantly deprived of the right to live in our homeland.

And all these suffering began centuries ago. In fact, when Crimea was first annexed in 1783. At that time, 98% of the local population in Crimea were Crimean Tatar People. One hundred of thousands of those who actively opposed the annexation were killed, religious rights were seized, many schools were closed, property was confiscated, archives were burned and culture was subjected to genocide.

On our mother’s line Zera and I descended Murz Karashaysky. Crimean Tatar Murza is a title equal to the prince/princess. This is the dynasty that had influence on the state administration of the Crimean state. Our aristocratic ancestors who had lands and rich possessions in Crimea lost everything because of the Russian empress. She decided to launch a geopolitical project in Crimea. Named Tavrida, based on imperial splendor, she started by labeling us barbarians, gradually erasing our history, culture and our heritage, all that reminded about Crimean Tatars.

ZAREMA: However, in May 1944, our people were faced with even more difficult days. The Soviet Union, led by dictator Joseph Stalin and his inner circle, committed genocide. He ordered the forced deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar population in just two days. While our grandparents Umer and Ridván fought against Nazism, all our defenseless women, children, and elderly were loaded onto cattle transport and transported to Central Asian countries. Our grandmother Levise was 7 years old when Soviet law enforcement broke into her house in the village of Baidary at 5 am on May 18, 1944. This village is now called Угловое. In connection with the deportation, her mother, brothers, and sisters were given only 15 minutes to gather without any explanation.

Our relatives were gathered from all over Crimea, assembled at railway stations, loaded like animals into cattle cars, and taken to Uzbekistan on a deadly journey that lasted almost a month. People died from suffocation, lack of food and water, and the bodies of the dead were simply thrown onto the road. The most cynical part of this story was that Stalin justified his crimes by calling Crimean Tatars a nation of traitors. However, as archives confirm, the order to deport was given first, and a reason was issued weeks later. Stalin’s real goal was to erase all indigenous national identities throughout the Soviet Union. His twisted ambition was to create a unified Soviet people devoid of uniqueness, united by the Russian language, distorted historical data, and propaganda.

ZERA: Another inhuman and utopian ideology that claimed the lives of many settlers was the imprisonment of millions of people. One of the imprisoned dissidents was our leader, Mustafa Cemilev. When the deportation took place, he was only one year old. He experienced all the difficulties alongside his people, and his greatest dream, like the dreams of thousands of other Crimean Tatar dissidents, was to return home. Because of this dream, he spent 15 years in Soviet prisons and camps, surviving 303 days of hunger strikes. All this because we wanted to return home. In exile, the Crimean Tatar people were not allowed to leave their places of exile; our relatives lived in concentration camps – special barracks without humane conditions, where they simply died of disease. As a result of the deportation, every second Crimean Tatar died.

ZAREMA: Our’s grandfather’s Mom and little brother was killed by injections in the hospital in one day. Our grandfather managed to escape this lethal injection; he fled when he saw his family being taken from the medical room one by one, covered with sheets. So he was left alone. And for the rest of his life, he didn’t trust the medical staff even in Crimea. This genocide killed 46.3% of the population.

Crimean Tatar People were not allowed to leave their places of exile until Stalin’s sudden death.

While all deportation’s peoples were returning to their homelands , only the Crimean Tatar People were not allowed to do this. The Soviet regime tried to forcibly assimilate them, dissolve them, but the Crimean Tatar People are like that flower that grows through a rock. We are still alive and we have survived.

ZERA: When the Soviet Union collapsed, the Crimean Tatar people began returning to their homeland, and our family came back to Crimea with three children and grandparents. It was a difficult time for entire people in the 90s in Crimea; other people lived in our grandparents’ homes, and the local population greeted us unfriendly. As 5-year-old kids, we lived in tents for 3-4 months because the local population did not rent apartments to Crimean Tatar people and didn’t want to employ them, hoping that indigenous people would leave the homeland due to the lack of conditions. Each of us had to go through 7 circles of hell.

ZAREMA: One day, our grandfather said he wanted to show us his village and the house where he was born and grew up in Bakhchisarai. When we got to the house, our grandfather stood in front of the family door for a long time, as if memories overwhelmed him. He was very upset and knocked on the familiar door. After 45 years, the new owners turned out to be his neighbors, who immediately recognized him. But they started shouting at him to leave; we all were confused. He stepped away from us so we wouldn’t see his pain, and there, on the side, we saw tears streaming down his cheeks. It was hard for us to see him like that. When Zera and I came up to him to hug him, he said that a few minutes in his yard have brought him a breath of air from memories of a happy his childhood when everyone was alive. He placed his palms on our hearts and said that there is a light within each of us, and we must hold onto this light in every difficult moment, because this light guides our path.

Father and Grandfather built a house on a small plot of land they purchased in a village far away from Bakhchisarai. We remember as soon as we moved into the house and woke up the next morning, our mother called us outside and said: “Girls, welcome the first Crimean snow.” We remember this moment as if it were yesterday.

ZERA: One day our brother came home from school with a torn jacket. When our mother asked what happened, our brother ran away without saying a word. A week later, we learned that during class the class teacher grabbed him by the collar to punish him for speaking Crimean Tatar in class. He was in 4th grade. This attitude towards the Crimean Tatars was general ksenofob position in the homeland.

My sister and I enrolled to universities back home in Simferopol. During this period, the Orange Revolution began – Crimean Tatars supported Yushchenko because he promised in his election campaigns that he would restore all rights to the Crimean Tatars. 15 I was one Crimean Tatar in my group, it was obvious that I was not for Yanukovych. And because of my Pro-Ukrainian side all professors of the university were lowed my grades and then I decided to transfer to the University of Kiev, so as not to feel bullied to myself. I moved to Kiev and I started learning and building my life there.

ZAREMA: My university was more loyal to my choice of president, but when I decided to get an internship, the head of the bank in my face told me that according to the rules of the company can not hire people of Crimean Tatar nationality. At the family council it was decided to follow my sister to Kiev.

And we could have had more joyful moments and happiness to share with you if not for another tragedy, the tragedy of the 2014 occupation. Yet another Moscow dictator decided to launch his own geopolitical project in Crimea based on Russian military grandeur. He turned my homeland into a prison, an open-air prison, where anyone who dared to publicly say that Crimea is Ukraine could be imprisoned for at least 15-20 years on terrorism charges. Because of this repressive reality, many thousands of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians started to flee the peninsula. For example, our friend’s son received a 7-year sentence for sending $14 to a card for a friend who served in the Ukrainian battalion Noman Celebidzhikhan. His name is Appaz, and he is the youngest prisoner there.

ZERA: Because of this repressive reality, ethnic Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars are facing danger. Threats, harassments, imprisonments, disappearances, and torture are forcing the indigenous people to leave their homeland. This situation mirrors what happened in Imperial and Soviet times, and now under the Russian Federation. The first victim of the 2014 occupation was a 33-year-old man named Reshat Ametov, a Crimean Tatar and father of three. He protested alone in Simferopol’s Central Square, supporting Ukraine. He was arrested and taken somewhere unknown. Two weeks later, we found him dead and mutilated.

ZAREMA: At that moment, my sister and I realized our loved ones were in danger. Our father had worked at a school for over 25 years, but everything changed when the Russian world came to Crimea. The new government and the new pro-Russian director started imposing their laws and oppressing those who supported Ukraine at the school. It was harsh psychological pressure. The work environment where he had worked for 25 years became hostile. Stressful situations at the school happened one after another. We begged him to go to Kiev, but he believed that Ukraine would return to Crimea tomorrow, and we would all be free again.

ZERA: After his death, about 2,000 students came to say goodbye to him. For seven years, our father’s disciples have been coming to our house for his birthday. They tell our mom funny stories about Dad, how pupils loved him and respected him. Yeah. We were broken up wanted to screaming our pain. We miss him every day, and we are sad that he will not see his grandchildren, a liberated Crimea, or justice for the Crimean Tatars.

ZAREMA: We, as daughters of our people, have learned not to give in to fear and sadness. Our belief in justice drives us. We continue to fight propaganda and disinformation, sharing the truth about the Crimean Tatars. To do this, we have created a YouTube channel where we share information about the life of our people in Crimea and document Russia’s violations. 21 We actively participate in various platforms. It is for these actions that we have been blacklisted by Russia. We know that if we try to enter Crimea, we’ll be imprisoned, like other activists (Lenie Umerova, Appaz Kurtametov, Edem Bekirov etc.)

ZERA: When Russia started a full-scale war in Ukraine, we started receiving death threats from unknown persons. In the first week of the war we sat in an unfamiliar basement, afraid to go outside. Butcha was happening nearby. We were full of fear, and at that moment panic attacks began. It was impossible to leave Kiev. Stations were crowded with women and children. The roads were full of traffic. Petrol was already in short supply. When we finally got out of the basement, we saw tanks passing through the windows and we heard the separatists marking houses for rocket attacks. This moment will be remembered forever.

ZAREAMA: This is the sound of danger, the sound of death, the sound of uncertainty, the sound of alarm. When we hear this sound, it means that Russia is launching its missiles or drones at our peaceful cities. When this dreadful sound echoes in the middle of the night, it’s a loud reminder that you could lose your life, your loved ones, or your home. Yes, we were really scared when the invasion began. At first, panic set in for each of us, but we didn’t allow this fear to paralyze us, and the whole nation, armed forces, volunteers, journalists, everyone, 24/7 defended our country. In the early days of the war, we, as marketers and IT specialists, organized a group on Telegram where we removed online tags in Google maps placed by Russian IT specialists on civilian objects throughout Ukraine.

We also said goodbye to life when a missile was flying towards us, which our air defense forces shot down. All this happened in front of our eyes, and we had no idea if we would survive. Bucha, Kherson, Irpin, and other worthy cities of Ukraine, the city of Mariupol became a death trap for thousands of Ukrainians. Mass graves, abductions, torture, filtration camps, rapes, and death – this is what we went through during 2 years of horrible war, but we survived. We turned our pain into our strength, our trauma into our resistance, our grief into determination to fight for our home. If you’ve ever seen a sunbeam break through the clouds on a rainy day, you’ve seen the image of our country, Ukraine, not as a victim, but as a nation breaking through with dignity. Our collective and my personal trauma with Zera has taught us one thing.

ZERA: Home is more than just a spot on the map; it’s a place where our hearts feel calm and our dreams come alive. It’s where we keep our memories safe and our future bright. Home is our stronghold, where we protect what we love. It’s full of hope, love, and precious memories.

The role of Crimean Tatars in the history of Crimea and their attitude to this territory

Historical context

In the heart of Eastern Europe, where history and geopolitics intersect, there is a story that begs to be told, the story of a people whose resilience and determination defy all odds. These are the Crimean Tatars, an indigenous people with a rich and long history, just like the land they rightfully call home. Today, however, they once again face an existential threat that demands the world’s attention.

A Rich Tapestry of History:

The Crimean Tatars are a testament to the peninsula’s diverse history, with their origins intertwining with the likes of about 28 nations and ethnic groups: the Taurians, Greeks, Scythians, Genoese, Pechenegs, Polovtsians and many more, forming a unique cultural amalgamation. Their heritage is a mosaic of influences, reflecting the rich history of the Crimean Peninsula itself. (1)

The Crimean Tatars, as their name suggests, are the Muslim inhabitants of Crimea.

Ibn Bibi, the author of the chronicles, emphasizes that the Islamization of the peninsula began in the 13th century. New institutions appear en masse – mosques, madrassas; a system of hierarchy of ministers is created – muftis, qadiaskers (supreme judges on military and religious issues), imams, khatibs (clergyman who performs Friday prayers).

During the Crimean Khanate Age, the culture of Crimean Tatars reached new heights, and a plethora of famous scientists appeared. In particular, their scientific works are referred to by leading scientists of Saudi Arabia and still today, quoting the works of the XIV century. (2)

First Occupation of Crimea 1783

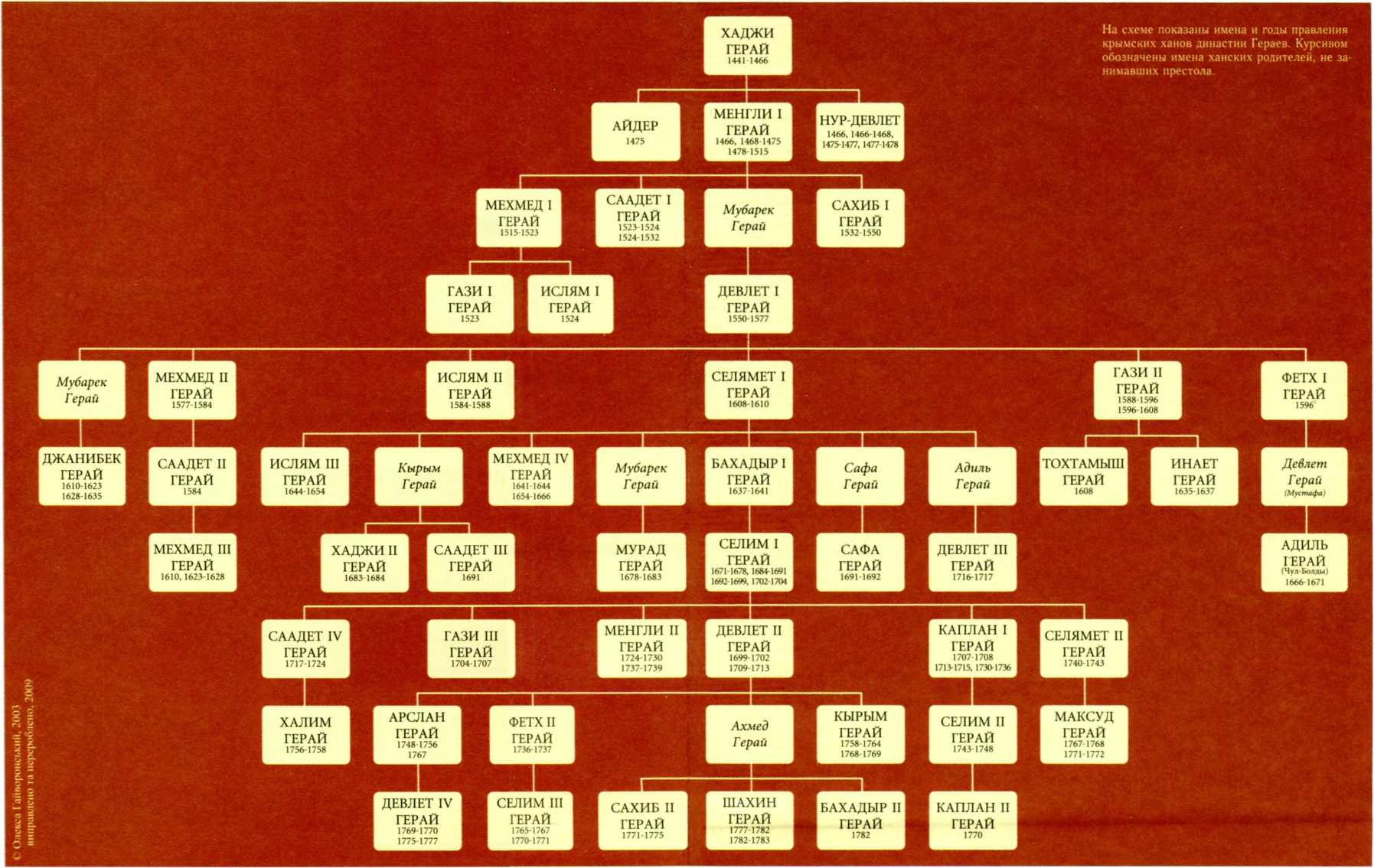

In 1441, the Crimean Khan Mengli Girey (born in Lithuania in 1389) concluded a military and political alliance with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Russia (Kievan Rus). For 3.5 centuries, the Crimean Tatars thrived independently, governing their own state until the Russian Empire’s occupation in 1783 (3).

In imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet historiography, the legality of the annexation lacks both a scholarly-historical and a practical (state-legal) basis. There is a direct violation of international law, at least on two counts. The Russian invasion of Crimea constitutes a breach of the international Küçük Kaynarca Treaty, and secondly, there is no official document signed regarding the transfer of Crimea. (4) The Russian occupation marked the beginning of a dark chapter in the Crimean Tatars’ history, characterized by systematic attempts to erase indigenous people of Crimea and their cultural, spiritual identity. Schools, mosques, archives and even tombstones bore the brunt of this brutal campaign. (5)

Genocidal Deportation and Exile: A Tragic History of Crimean Tatars 1944

The most harrowing chapter in the Crimean Tatars’ history unfolded during World War II.

Stalin’s totalitarian regime was constantly looking for and finding culprits. They were different in different periods. But there were always reasons to justify such a policy – and they were sometimes even phantasmagorical. With regard to the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, they were formulated in the GKO Resolution No. 5859ss (classified as “top secret”) “On the Crimean Tatars” of May 11, 1944.(6)

In 1944, under the pretext of collaboration with the Nazis, the entire Crimean Tatar population faced forced deportation. This genocidal act claimed the lives of 46.3% of the Crimean Tatars, leaving scars that still haunt survivors and their descendants today. Nearly half of the Crimean Tatar population perished during this horrific event (46.3%) (7). During this genocide deportation, children and the elderly died in cattle cars, women gave birth on the road, and children did not survive and died due to the terrible conditions, 70% were died children (8). At the places of exile, the Crimean Tatars were subjected to cruel curfew supervision and legal restrictions that contributed to the mass deaths and cultural degradation of the Crimean Tatars. Only Crimean Tatars retained the right to slave labor. Only in the first years after the expulsion, the Crimean Tatars lost about 46.3 percent of their number from starvation, disease, and hard forced labor. This is a severe, unbearable, and open trauma that will reverberate for generations to come.

Meanwhile, Crimea was being hastily settled by immigrants from central Russia. All property of the Crimean Tatars was taken away during the eviction and distributed to new settlers. (9) In 1944, Russian propaganda began with renewed vigor, portraying Crimean Tatars in the most negative light. (10)

For five long decades, they were forbidden to return to their homeland, forced to rebuild their lives from the ground up. It took nearly half a century for them to return to their homeland after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.(11)

The Never-Ending Exodus 2014

The struggle of the Crimean Tatars did not end there. Their hope was short-lived. They found themselves back at the beginning of the journey, striving for a peaceful life in their homeland. In 2014, Russia’s occupation of Crimea shattered any illusions of stability, and discrimination, hatred, persecution, torture, and imprisonment of the indigenous people of Crimea began. (12)

Since then, the Russian government has intensified its campaign to annex Crimea to Russia, displacing indigenous people and replacing them with ethnic Russians. (13)

When Russia occupied Crimea again in 2014, it was a blatant violation of international agreements, including the Budapest Memorandum of 1994 (14). Ukraine had relinquished Soviet and nuclear weapons in exchange for guarantees of security and territorial integrity, which Russia betrayed.

The Need for International Action

The United Nations’ inability to prevent and stop such aggression is evident, largely due to the aggressor’s veto power. Russia openly defies international resolutions and decisions.(15)

The Crimean Tatars’ Plight in 2023

The oppression of the Crimean Tatars has escalated dramatically and become more frequent since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (16). Activists and protesters who dared to resist were met with threats, imprisonment, and even kidnappings in broad daylight. The story of Nariman Dzhelyal, the first deputy chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, exemplifies this. His participation in the Crimean Platform Summit resulted in a 17-year prison sentence, on trumped-up charges, leaving his three young children fatherless.(17)

Conclusion

A Brutal Reality

At first glance, there seems to be no connection between Reşat Amet, the first victim of the occupation of Crimea, and the hundreds of Ukrainians tortured in Bucha, Irpen and Izium – horrors that have shocked the world. But the connection is real.

The future system of international security must be based on the toughest possible response by governments and international organisations to human rights violations. This will allow us all to prevent such tragedies from being repeated. Governments that systematically violate human rights should be isolated from the civilised world. As we contemplate the Crimean Tatars’ plight, it is impossible to ignore the horrifying parallels to past genocides. Reading Muslim literature and expressing anti-government views can lead to 15-year prison sentences. Ethnic purges are happening before our eyes, and the Crimean Tatars are locked up, their voices silenced.(18)

In the face of oppression, the Crimean Tatars maintain their faith that justice will ultimately prevail. However, as the world watches, we must not allow more innocent lives to be lost. The time to act is now.

The Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev aptly remarks, “The reign of jackals lasts until the lions wake up and stand up.” They hope for justice to prevail, not brute force, and call upon the international community to stand with them.(19)

- Bibliography

- Gulnara Abdulaieva. “Crimean Tatars: From ethnogenesis to nationhood” p.12.

- https://risu.ua/ru/islam-v-krymu-zolotoe-proshloe-i-neopredelennoe-segodnya_n71602

- https://youtu.be/paBJ22uY30s?si=A-XGJL_sIPGx9WcC

- V.Vozgrin, II, History of Crimean Tatars p.384-385

- 5. Clarke, 1810. p.467, V.Vozgrin, II, History of Crimean Tatars p.394-431

- https://www.segodnya.ua/regions/krym/priyti-mogut-k-kazhdomu-intervyu-s-televedushchey-gulnaroy-bekirovoy-o-sudbe-krymskih-tatar-1139219.html

The Numbers Testify (mass-political publication) Historical Documents. 2012. p.307

Ernst Abduraimovich Kudusov https://youtu.be/f7LQKEx1Orc?si=SgHLHWUxZ_ROlIQt 9. Mustafa Cemiloglu, “The Beginning of the Crimean Tatar National Liberation Movement,” in Crimea: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects, ed. Maria Drohobycky (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995)

Gulnara Abdulaieva. “Crimean Tatars: From ethnogenesis to nationhood” 2021 p.6.

Rory Finnin “Blood of Others” 2022

12.https://www.rferl.org/a/abductions-torture-hybrid-deportation-crimean-tatar-activist-describes-six-years-under-russian-rule/30493504.html

13.https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-accused-of-reshaping-annexed-crimea-demographics-ukraine/29262130.html

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=0800000280401fbb

3:26:28 – 3:26:51 https://www.youtube.com/live/bV9iflsLAFw?si=UUC4I85U7ZXslGJk , https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15399.doc.htm

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/russia-ukraine-war-crimea-tatar-muslim-minority-kremlin-crackdown-rcna75016

5:25:27 https://www.youtube.com/live/TV5ZJTS_uwM?si=aHZSHUofLX1ixxT_

https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/columns/2023/03/15/7393446/

19. 3:21:00 -3:30:20 https://www.youtube.com/live/bV9iflsLAFw?si=UUC4I85U7ZXslGJk

Archival video of the 90s and a letter of recollection from a Crimean Tatar woman in November 2023

“It’s the year 1990.

I reminisce about our family’s return to our homeland, a time marked by hardship shrouded in the darkness of disbelief and injustice. I was young then, but even at that age, I already grasped that the world is far from always being fair.

In my memory, images of the cruelty of Russian occupiers in Crimea stand out. They infiltrated the homes of our grandparents, settling there like strangers in a foreign land. Upon returning to Crimea, our people didn’t abandon their fight for justice. We pleaded with the world to take notice, but it seemed we were still carried away by waves of indifference, reminiscent of the beastly gaze our ancestors faced when encountering Russians on their land two centuries ago.

And here we are again, facing the beast, but something has changed this time. The world heard us, Ukraine felt us, and finally, we became united. We must restore the strong Ukrainian-Crimean Tatar connections erased by the efforts of Russian historians. We must learn from how the Crimean Tatars preserved their uniqueness and humanity in resistance.

Today, we endure all the pains accompanying the struggle for our country. But this time, we have the ears and attention of the world. We understand what is happening in Ukraine not only on a rational level but also on a soulful level. Our determination to reclaim Ukrainian Crimea, liberate occupied territories, and cleanse Ukraine from Russian influence is our destiny.

The journey of return to the homeland for Crimean Tatars demands too much to tread it in vain. In this struggle, we must not lose our humanity, or victory will lose its meaning. We believe in the revival of Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar identity, and we are ready to defend our country and homeland despite all the challenges”.

Crimean Tatar Journalist and Scholar at Purdue University

Zera Mustafaieva

Source of archived video YouTube Channel “Crimea Speaks”

https://youtube.com/shorts/KFE1JLlfuX0?si=KvwPnBjKdUqFy2HA

Source of archived video Instagram Page “Crimean Tatar Foundation USA”

https://www.instagram.com/reel/CzjLR3kLuZB/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

MISSION OF CRIMEAN TATAR FOUNDATION USA

Zera Mustafaieva

PRESIDENT

Zarema Mustafaieva

COMMUNICATION CHAIR

Lilya Emirsaliyeva

VICE PRESIDENT

Lenie Useinova

CREATIVE CHAIR

JUSTICE AND PEACE

At the core of our hearts lies an unwavering commitment to justice and a vision for a peaceful future for our beloved people – the Crimean Tatars. As daughters of a resilient nation, our souls are inextricably linked with the destiny of our people. From the very first days of our lives, we have witnessed and shared the peaceful struggle of those who, for half a century, endured exile and injustice, while striving to return to their homeland in Crimea.

Our hearts burn with a burning desire to see the entire Crimean Tatar People regain their rightful place in the historical land they call home and regain the fundamental rights that were unjustly taken from them. It is the reason that lives deep within us, the unquenchable fire that fuels our every action.

Join us on this remarkable journey, where the pursuit of justice and the dream of peaceful coexistence form the bedrock of our efforts. Together, we can make a difference. Together, we can write a brighter future for the Crimean Tatar People and all those who yearn for a world where justice and peace prevail.

Zera Mustafaieva is a dedicated journalist, human rights activist, and scholar with a profound commitment to advocating for justice and human rights. With a background in reporting from the Ukrainian Parliament and expertise in social media marketing, she has been instrumental in raising awareness on critical issues.

As one of the founders of the influential YouTube Channel “Crimea Speaks,” Zera has provided a platform for the Crimean Tatar People to share their stories and perspectives with the world. Through this channel, she has chronicled the rich history and present struggles of the Crimean Tatar People, shedding light on their experiences and aspirations.

Zera’s passion for human rights extends beyond her journalism work. She is actively involved in volunteer initiatives, notably with “Razom for Ukraine,” where she contributes her time and energy to support the Ukrainian cause. In addition to her volunteer efforts, Zera is also the co-founder and president of the Ukrainian NGO “Space of Crimea,” where she works tirelessly to promote the rights and well-being of the Crimean Tatar People.

In pursuit of academic excellence and furthering her advocacy, Zera is a scholar at Purdue University, where she continues to expand her knowledge and skills in order to better serve her People. Her dedication to peaceful methods and her unwavering commitment to human rights make her a respected figure in both Ukraine and the global community.

Zarema Mustafaieva is a prominent journalist, human rights activist, and scholar known for her tireless efforts to promote justice, human rights, and the welfare of the Crimean Tatar People. With an impressive career that includes reporting from the Ukrainian Parliament and expertise in social media marketing, she has made significant contributions to the field of journalism and advocacy.

Together with her sister, Zarema co-founded the influential YouTube Channel “Crimea Speaks,” which has become a vital platform for amplifying the voices of the Crimean Tatar People. Through this channel, she has chronicled the history and current struggles of the Crimean Tatar People, bringing their stories to a global audience and advocating for their rights.

Zarema’s commitment to human rights is not limited to her journalistic endeavors. She actively engages as a volunteer with “Razom for Ukraine,” dedicating her time and energy to support Ukraine’s causes and humanitarian efforts. Furthermore, she is the co-founder and president of the Ukrainian NGO “Space of Crimea,” where she works tirelessly to advance the rights and well-being of the Crimean Tatar People.

Zarema’s dedication to promoting peace and respect for human rights has earned her recognition and respect both locally and internationally. As a scholar at Purdue University, she continues to deepen her understanding and expertise, further equipping herself to be a powerful advocate for the causes she holds dear.

All Roads lead to Crimea: Crimean Tatar anthem in Manhattan

Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars Unite in a Unique Cultural Event

The organizers: Razom For Ukraine, Crimean Tatar Foundation USA, and the co-organizers, the Ukrainian Institute and Сemiyet, partners Brighter Ukraine Foundation, Speakers: Mustafa Jemilev, Andriy Grigorenko, Mubein Altan, Walter Ruby, Zera and Zarema Mustafaieva

Agenda

Doors Open – 1:00 pm

Session Starts – 1:30 pm

Coffee & Sweets – 3:30 pm

Location

Ukrainian National Home

Manhattan, 140 2nd Ave, New York, NY 10003

One big event introduced Ukrainians and Americans to the world of Crimean Tatar heritage, enriched the cultural landscape and opened new horizons of understanding.

On July 1 at 1 p.m., the Ukrainian National Home hosted an exciting event that opened the door to learning about the rich and deep Crimean Tatar history and culture*.

We introduced Ukrainians and Americans to the richness of Crimean Tatar culture and shed light on the history and legacy that Crimean Tatars have left in this world. The event, which consisted of fascinating performances, exhibitions and concerts, provided a unique opportunity to delve deeper into an ethnographic journey and realize the significance of this people in the context of modern culture.

More than 200 people joined this cultural celebration and met with talented artists, researchers and cultural figures, sharing the joy of discovery and creating new threads of connection between Americans, Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars

СRIMEAN TATARS in Manhattan New York City / Crimea speaks / Zera Zarema

How the Crimean Tatar people live in Putin’s Crimea (2014-2023)

In 2014, when Russian troops occupied Crimea, the Crimean Tatars were among the most ardent opponents of Russia’s invasion of their homeland.

Since then, Crimean Tatars have been paying a high price for our disobedience.

“Crimean Tatars live in fear,” “As occupation, all our fears, all the tragedies that our people have suffered since 1944, have resurrec up.”

Crimean Tatars – and these are mainly Muslims of Turkic origin – make up about 12 percent of the two million population of Crimea.

In May 1944, by order of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the entire Crimean Tatar population was deported “for sympathy for Nazi Germany. Entire families were loaded into railway cars to transport livestock and went to Central Asia. 46,3 % of Crimean Tatars died as a result of this deportation.

Crimean Tatars were imagined “fully rehabilitated” in 1967, deportation remains a great trauma for the Crimean Tatars, many of whom still associate Russian rule with oppression and suffering.

Persecution of Crimean Tatars began soon after the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. Activists and protesters are harassed, threatened, imprisoned for 15 years, and in some cases even kidnapped in broad daylight. On 15 March 2014, the mutilated body of Reshat Ametov, a Crimean Tatar who was abducted while peacefully demonstrating against the Russian occupation, was found outside Simferopol.He was buried on 18 March, the day Putin triumphantly announced the annexation of Crimea, promising to protect all ethnic groups on the peninsula. Ametov’s murder sent shockwaves through the Crimean Tatar people. This is when we became really scared,“We felt and feel scared and completely unprotected of our people. Over the next year, more than 30 Crimean Tatars went missing. At least six of them, including Ametov, have since turned up dead. Others remain unaccounted for.

At the same time, russia was quick to crack down on Crimean Tatars’ distinctive culture and sense of identity. Because of the risk of repression, we Crimean Tatar people can only express our family anger and pain in closed circles.

A new Russian law imposing prison sentences of up to 15 years for disseminating information that contradicts the authorities’ view of the war in Ukraine has made dissent in Crimea even more dangerous.

Now the same Auschwitz is taking place in Crimea, Crimean Tatars are being killed and prisons for religious and political reasons, ethnic purges, repressions of the indigenous people.

Today there are more Crimean Tatar political prisoners than Russian political prisoners, there are 300 thousand of us and 146 million Russians. More than 1000 children were left without fathers.

Crimean Tatar media outlets were shut down or turned into Russian-language Kremlin mouthpieces. The Crimean Tatar language all but disappeared from the public sphere. The Mejlis, the representative body of the Crimean Tatars, was declared “extremist” and disbanded, and its leaders were forced into exile.

In one of the most painful blows to Crimean Tatars people were banned from marking the anniversary of our people’s Stalin-era genocide.

For 30 years we had gathered on squares in our cities to pay tribute to the victims,” “Today we are no longer allowed to hold these commemorations. We can’t even grieve гand honour our dead.”

Putin’s current war against Ukraine is a devastating reminder of the invasion of Crimea nine years ago, which we believe paved the way for today’s tragedy.

Due to the risk of reprisals, Crimean Tatars can only express in their family anger and pain in private circles.

A new Russian law imposing prison terms of up to 15 years for spreading information that contradicts the authorities’ narrative about the war in Ukraine has made dissent even more dangerous in Crimea.

“Crimean Tatars want to scream but we need to keep silent,”. “Our people are locked up.

Genetic origins of the Crimean Tatars and their relationship to the Mongols

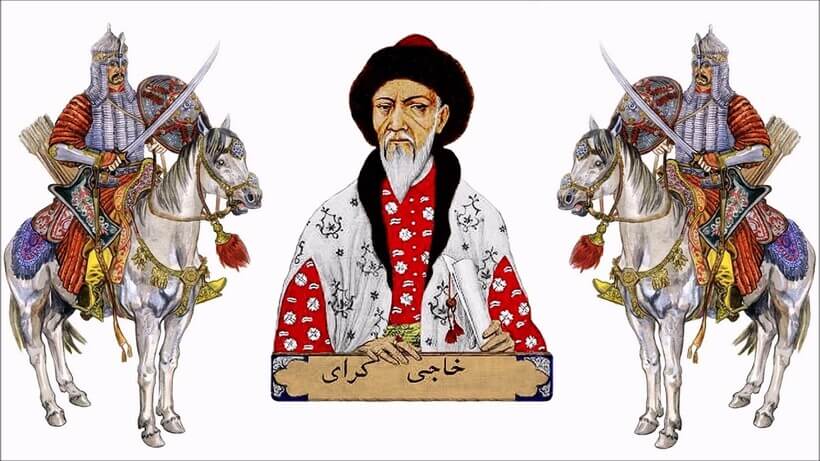

The founder of the Crimean Khanate in 1441, Melek Hacı Geray, was born in 1397 within the borders of Lithuania. His parents, political emigrants seeking refuge in Lithuania, had fled the turbulent feuds of the Golden Horde. Thus, a direct descendant of Genghis Khan found himself in the heart of Europe. Growing up amidst the cultural tapestry of Lithuania, Hadji Giray received a well-rounded education by the standards of his time.

When the Crimean Tatars sought of a leader for their future nascent Khanate, they turned to Hadji Giray. His dual identity as a leader and an heir to the Golden Horde made him the perfect candidate to assert their legitimate rights to the inheritance of the Golden Horde.

In 1441, Hadji Giray assumed the mantle of leadership as the first Khan of the Crimean Khanate. He cemented his authority by forging a strategic military and political alliance with both the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Rus’ (Kyivan Rus’). The Moscovites paid tribute to the Crimean Khanate for a span of 300 years.

The basis of Khanate was the indigenous people – Crimean Tatars descendants of Scythians, Goths, Taurians, Greeks, Italians, Seljuks, Polovtsians, Pechenegs – about 28 peoples and ethnicities. The Mongols who were in the administration quickly assimilated into the people of the Crimean Tatars.

Every Crimean Tatar is a living historical document, reflecting the complex mosaic heritage of this region. Their blood carries traces of Scythians, Goths, Taurians, Greeks, Italians, Seljuks, Polovtsians, Pechenegs, and many other peoples who have left their mark on this land. This unique cultural symbiosis not only makes Crimean Tatars the heirs of history but also the custodians of a multifaceted legacy they proudly pass down to future generations.