From Tragedy to Strength: Personal Story of Survival and Fight for Home

We are Zera and Zarema. We are representatives of the historical titular nation of Crimea and the indigenous PEOPLE of Ukraine – Crimean Tatars. We are daughters of our nation, daughters of our country. We want to confess to you in that article. This article is about our personal story. The story of our family and the story of our indigenous people of Ukraine and an under-discovered Nation who went through oppressions and colonization for centuries and the historical titular nation of Crimea who was born out of a mixture of all tribes and people ever inhabited the peninsula.

ZAREMA: A couple of weeks ago, we got a call from our grandmother. She’s 87 years old and currently in Crimea. This call influenced our specific understanding of what we wanted to write in that article . Our grandparents, relatives and all our ethnic Ukrainians friends have been living under occupation since 2014. Since the beginning of the occupation, our Grandmother Leviza has never stopped believing that justice will prevail and Ukraine will return to Crimea.

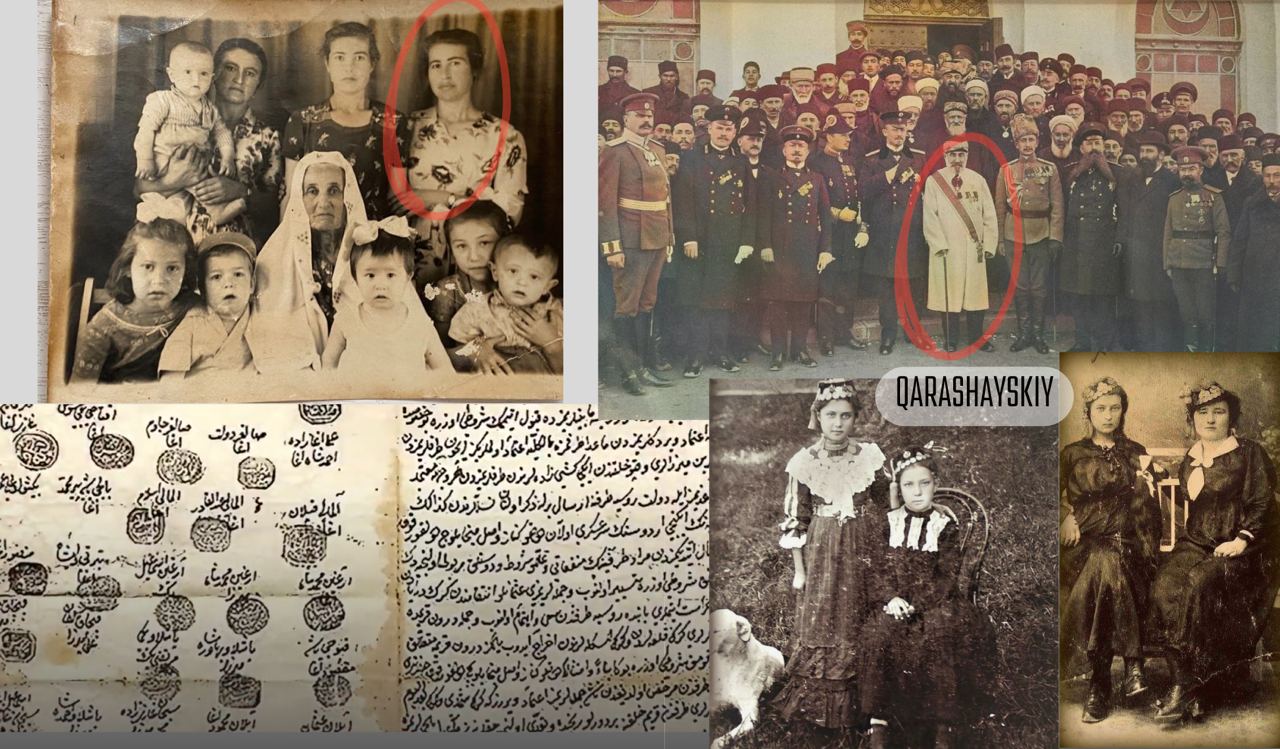

Our grandmother is from a noble aristocratic family of the Karashaysky (Qarashaysky) dynasty – she is a strong-spirited and unwavering woman. We have always seen her as an example of resilience and self-control. She says we represent our nation and should set an example for others

But this time, our grandmother was crying. She confessed to us that she has been looking at the door of her house more often, expecting Russian soldiers to burst in at any moment, as it was in her childhood, put her into deadly wagons for a month without food and water, and take her away from her homeland, as it was in 1944. She said, “Granddaughters, I can’t take it anymore. I want all this to end like a terrible dream.” Our tears flowed because we realized that we cannot make grandma feel peaceful and happy, we cannot erase the bad memories from her heart. We cannot stop what is happening now in occupied Crimea.

Among our roles as activists, human rights defenders, and journalists, we, as daughters of our people and heirs of the noble Karashaysky family, feel the need to share another aspect of our lives. As sisters, we want to share our pain, our wounds, and to reveal our personal experiences and thoughts about the war. Today, in this moment, all we want to convey is our personal history.

It is the story of Crimean Tatar children born in conditions of forced exile, far from their homeland of Crimea. It is the story of sisters who grew up in their homeland in Crimea, who feeling like outsiders in their own land, all because of Russian propaganda. It is the narrative of schoolgirls who were bullied by both classmates and teachers because of their nationality. It is the story of female students who were denied the opportunity to be employed in Crimea simply because of their nationality. It is the saga of daughters whose father was taken by the Russian authorities in Crimea. This is the story of Ukrainian activists who were banned from entering Crimea in 2017. It is the tale of the regular search for a home, the story of losing a home, and the history of the collective trauma ingrained in the DNA of every Crimean Tatar, as we were constantly deprived of the right to live in our homeland.

And all these suffering began centuries ago. In fact, when Crimea was first annexed in 1783. At that time, 98% of the local population in Crimea were Crimean Tatar People. One hundred of thousands of those who actively opposed the annexation were killed, religious rights were seized, many schools were closed, property was confiscated, archives were burned and culture was subjected to genocide.

On our mother’s line Zera and I descended Murz Karashaysky. Crimean Tatar Murza is a title equal to the prince/princess. This is the dynasty that had influence on the state administration of the Crimean state. Our aristocratic ancestors who had lands and rich possessions in Crimea lost everything because of the Russian empress. She decided to launch a geopolitical project in Crimea. Named Tavrida, based on imperial splendor, she started by labeling us barbarians, gradually erasing our history, culture and our heritage, all that reminded about Crimean Tatars.

ZAREMA: However, in May 1944, our people were faced with even more difficult days. The Soviet Union, led by dictator Joseph Stalin and his inner circle, committed genocide. He ordered the forced deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar population in just two days. While our grandparents Umer and Ridván fought against Nazism, all our defenseless women, children, and elderly were loaded onto cattle transport and transported to Central Asian countries. Our grandmother Levise was 7 years old when Soviet law enforcement broke into her house in the village of Baidary at 5 am on May 18, 1944. This village is now called Угловое. In connection with the deportation, her mother, brothers, and sisters were given only 15 minutes to gather without any explanation.

Our relatives were gathered from all over Crimea, assembled at railway stations, loaded like animals into cattle cars, and taken to Uzbekistan on a deadly journey that lasted almost a month. People died from suffocation, lack of food and water, and the bodies of the dead were simply thrown onto the road. The most cynical part of this story was that Stalin justified his crimes by calling Crimean Tatars a nation of traitors. However, as archives confirm, the order to deport was given first, and a reason was issued weeks later. Stalin’s real goal was to erase all indigenous national identities throughout the Soviet Union. His twisted ambition was to create a unified Soviet people devoid of uniqueness, united by the Russian language, distorted historical data, and propaganda.

ZERA: Another inhuman and utopian ideology that claimed the lives of many settlers was the imprisonment of millions of people. One of the imprisoned dissidents was our leader, Mustafa Cemilev. When the deportation took place, he was only one year old. He experienced all the difficulties alongside his people, and his greatest dream, like the dreams of thousands of other Crimean Tatar dissidents, was to return home. Because of this dream, he spent 15 years in Soviet prisons and camps, surviving 303 days of hunger strikes. All this because we wanted to return home. In exile, the Crimean Tatar people were not allowed to leave their places of exile; our relatives lived in concentration camps – special barracks without humane conditions, where they simply died of disease. As a result of the deportation, every second Crimean Tatar died.

ZAREMA: Our’s grandfather’s Mom and little brother was killed by injections in the hospital in one day. Our grandfather managed to escape this lethal injection; he fled when he saw his family being taken from the medical room one by one, covered with sheets. So he was left alone. And for the rest of his life, he didn’t trust the medical staff even in Crimea. This genocide killed 46.3% of the population.

Crimean Tatar People were not allowed to leave their places of exile until Stalin’s sudden death.

While all deportation’s peoples were returning to their homelands , only the Crimean Tatar People were not allowed to do this. The Soviet regime tried to forcibly assimilate them, dissolve them, but the Crimean Tatar People are like that flower that grows through a rock. We are still alive and we have survived.

ZERA: When the Soviet Union collapsed, the Crimean Tatar people began returning to their homeland, and our family came back to Crimea with three children and grandparents. It was a difficult time for entire people in the 90s in Crimea; other people lived in our grandparents’ homes, and the local population greeted us unfriendly. As 5-year-old kids, we lived in tents for 3-4 months because the local population did not rent apartments to Crimean Tatar people and didn’t want to employ them, hoping that indigenous people would leave the homeland due to the lack of conditions. Each of us had to go through 7 circles of hell.

ZAREMA: One day, our grandfather said he wanted to show us his village and the house where he was born and grew up in Bakhchisarai. When we got to the house, our grandfather stood in front of the family door for a long time, as if memories overwhelmed him. He was very upset and knocked on the familiar door. After 45 years, the new owners turned out to be his neighbors, who immediately recognized him. But they started shouting at him to leave; we all were confused. He stepped away from us so we wouldn’t see his pain, and there, on the side, we saw tears streaming down his cheeks. It was hard for us to see him like that. When Zera and I came up to him to hug him, he said that a few minutes in his yard have brought him a breath of air from memories of a happy his childhood when everyone was alive. He placed his palms on our hearts and said that there is a light within each of us, and we must hold onto this light in every difficult moment, because this light guides our path.

Father and Grandfather built a house on a small plot of land they purchased in a village far away from Bakhchisarai. We remember as soon as we moved into the house and woke up the next morning, our mother called us outside and said: “Girls, welcome the first Crimean snow.” We remember this moment as if it were yesterday.

ZERA: One day our brother came home from school with a torn jacket. When our mother asked what happened, our brother ran away without saying a word. A week later, we learned that during class the class teacher grabbed him by the collar to punish him for speaking Crimean Tatar in class. He was in 4th grade. This attitude towards the Crimean Tatars was general ksenofob position in the homeland.

My sister and I enrolled to universities back home in Simferopol. During this period, the Orange Revolution began – Crimean Tatars supported Yushchenko because he promised in his election campaigns that he would restore all rights to the Crimean Tatars. 15 I was one Crimean Tatar in my group, it was obvious that I was not for Yanukovych. And because of my Pro-Ukrainian side all professors of the university were lowed my grades and then I decided to transfer to the University of Kiev, so as not to feel bullied to myself. I moved to Kiev and I started learning and building my life there.

ZAREMA: My university was more loyal to my choice of president, but when I decided to get an internship, the head of the bank in my face told me that according to the rules of the company can not hire people of Crimean Tatar nationality. At the family council it was decided to follow my sister to Kiev.

And we could have had more joyful moments and happiness to share with you if not for another tragedy, the tragedy of the 2014 occupation. Yet another Moscow dictator decided to launch his own geopolitical project in Crimea based on Russian military grandeur. He turned my homeland into a prison, an open-air prison, where anyone who dared to publicly say that Crimea is Ukraine could be imprisoned for at least 15-20 years on terrorism charges. Because of this repressive reality, many thousands of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians started to flee the peninsula. For example, our friend’s son received a 7-year sentence for sending $14 to a card for a friend who served in the Ukrainian battalion Noman Celebidzhikhan. His name is Appaz, and he is the youngest prisoner there.

ZERA: Because of this repressive reality, ethnic Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars are facing danger. Threats, harassments, imprisonments, disappearances, and torture are forcing the indigenous people to leave their homeland. This situation mirrors what happened in Imperial and Soviet times, and now under the Russian Federation. The first victim of the 2014 occupation was a 33-year-old man named Reshat Ametov, a Crimean Tatar and father of three. He protested alone in Simferopol’s Central Square, supporting Ukraine. He was arrested and taken somewhere unknown. Two weeks later, we found him dead and mutilated.

ZAREMA: At that moment, my sister and I realized our loved ones were in danger. Our father had worked at a school for over 25 years, but everything changed when the Russian world came to Crimea. The new government and the new pro-Russian director started imposing their laws and oppressing those who supported Ukraine at the school. It was harsh psychological pressure. The work environment where he had worked for 25 years became hostile. Stressful situations at the school happened one after another. We begged him to go to Kiev, but he believed that Ukraine would return to Crimea tomorrow, and we would all be free again.

ZERA: After his death, about 2,000 students came to say goodbye to him. For seven years, our father’s disciples have been coming to our house for his birthday. They tell our mom funny stories about Dad, how pupils loved him and respected him. Yeah. We were broken up wanted to screaming our pain. We miss him every day, and we are sad that he will not see his grandchildren, a liberated Crimea, or justice for the Crimean Tatars.

ZAREMA: We, as daughters of our people, have learned not to give in to fear and sadness. Our belief in justice drives us. We continue to fight propaganda and disinformation, sharing the truth about the Crimean Tatars. To do this, we have created a YouTube channel where we share information about the life of our people in Crimea and document Russia’s violations. 21 We actively participate in various platforms. It is for these actions that we have been blacklisted by Russia. We know that if we try to enter Crimea, we’ll be imprisoned, like other activists (Lenie Umerova, Appaz Kurtametov, Edem Bekirov etc.)

ZERA: When Russia started a full-scale war in Ukraine, we started receiving death threats from unknown persons. In the first week of the war we sat in an unfamiliar basement, afraid to go outside. Butcha was happening nearby. We were full of fear, and at that moment panic attacks began. It was impossible to leave Kiev. Stations were crowded with women and children. The roads were full of traffic. Petrol was already in short supply. When we finally got out of the basement, we saw tanks passing through the windows and we heard the separatists marking houses for rocket attacks. This moment will be remembered forever.

ZAREAMA: This is the sound of danger, the sound of death, the sound of uncertainty, the sound of alarm. When we hear this sound, it means that Russia is launching its missiles or drones at our peaceful cities. When this dreadful sound echoes in the middle of the night, it’s a loud reminder that you could lose your life, your loved ones, or your home. Yes, we were really scared when the invasion began. At first, panic set in for each of us, but we didn’t allow this fear to paralyze us, and the whole nation, armed forces, volunteers, journalists, everyone, 24/7 defended our country. In the early days of the war, we, as marketers and IT specialists, organized a group on Telegram where we removed online tags in Google maps placed by Russian IT specialists on civilian objects throughout Ukraine.

We also said goodbye to life when a missile was flying towards us, which our air defense forces shot down. All this happened in front of our eyes, and we had no idea if we would survive. Bucha, Kherson, Irpin, and other worthy cities of Ukraine, the city of Mariupol became a death trap for thousands of Ukrainians. Mass graves, abductions, torture, filtration camps, rapes, and death – this is what we went through during 2 years of horrible war, but we survived. We turned our pain into our strength, our trauma into our resistance, our grief into determination to fight for our home. If you’ve ever seen a sunbeam break through the clouds on a rainy day, you’ve seen the image of our country, Ukraine, not as a victim, but as a nation breaking through with dignity. Our collective and my personal trauma with Zera has taught us one thing.

ZERA: Home is more than just a spot on the map; it’s a place where our hearts feel calm and our dreams come alive. It’s where we keep our memories safe and our future bright. Home is our stronghold, where we protect what we love. It’s full of hope, love, and precious memories.

All Roads lead to Crimea: Crimean Tatar anthem in Manhattan

Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars Unite in a Unique Cultural Event

The organizers: Razom For Ukraine, Crimean Tatar Foundation USA, and the co-organizers, the Ukrainian Institute and Сemiyet, partners Brighter Ukraine Foundation, Speakers: Mustafa Jemilev, Andriy Grigorenko, Mubein Altan, Walter Ruby, Zera and Zarema Mustafaieva

Agenda

Doors Open – 1:00 pm

Session Starts – 1:30 pm

Coffee & Sweets – 3:30 pm

Location

Ukrainian National Home

Manhattan, 140 2nd Ave, New York, NY 10003

One big event introduced Ukrainians and Americans to the world of Crimean Tatar heritage, enriched the cultural landscape and opened new horizons of understanding.

On July 1 at 1 p.m., the Ukrainian National Home hosted an exciting event that opened the door to learning about the rich and deep Crimean Tatar history and culture*.

We introduced Ukrainians and Americans to the richness of Crimean Tatar culture and shed light on the history and legacy that Crimean Tatars have left in this world. The event, which consisted of fascinating performances, exhibitions and concerts, provided a unique opportunity to delve deeper into an ethnographic journey and realize the significance of this people in the context of modern culture.

More than 200 people joined this cultural celebration and met with talented artists, researchers and cultural figures, sharing the joy of discovery and creating new threads of connection between Americans, Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars

СRIMEAN TATARS in Manhattan New York City / Crimea speaks / Zera Zarema