June 28, 2025

Keywords: US Constitution, Crimean Tatar Constitution, Democratic East, Civilized World

📖 15 min read | 🏷️ History • Democracy • Geopolitics • Indigenous Rights • Constitutional Law

A forgotten chapter in the history of democratic governance unfolds in the palaces of Bakhchisaray, where Crimean Tatars developed a sophisticated system of checks and balances centuries before the founding fathers

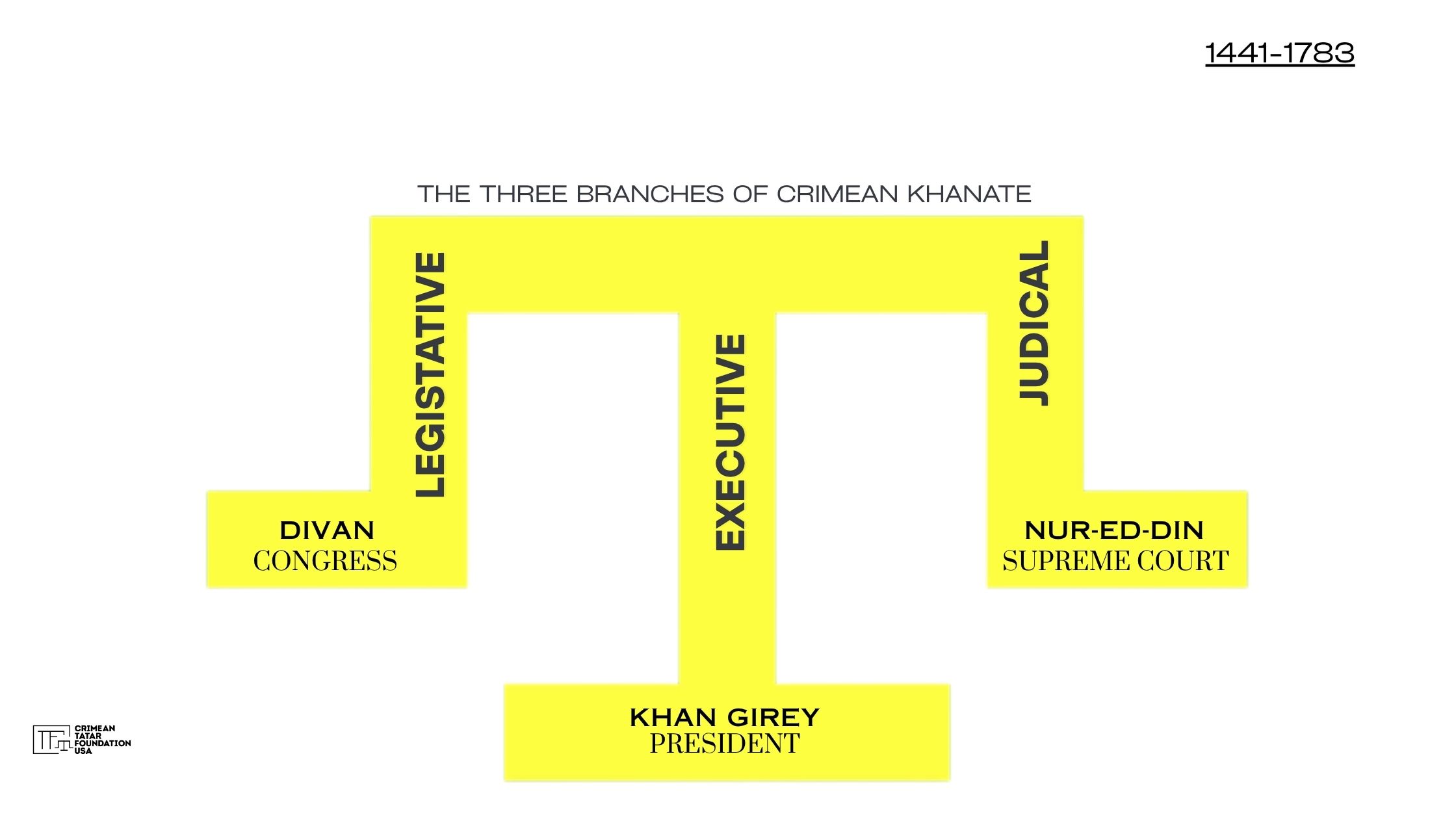

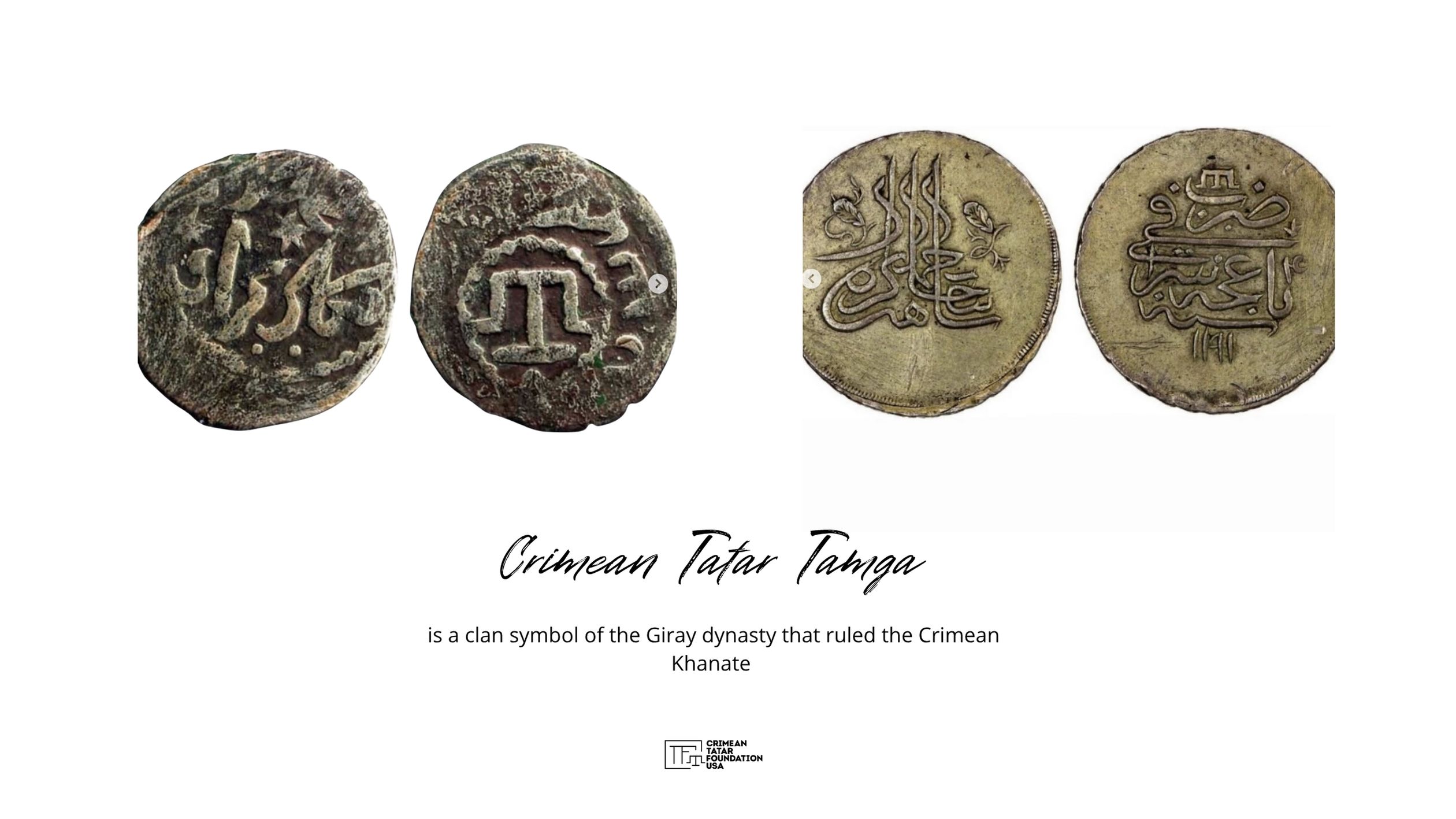

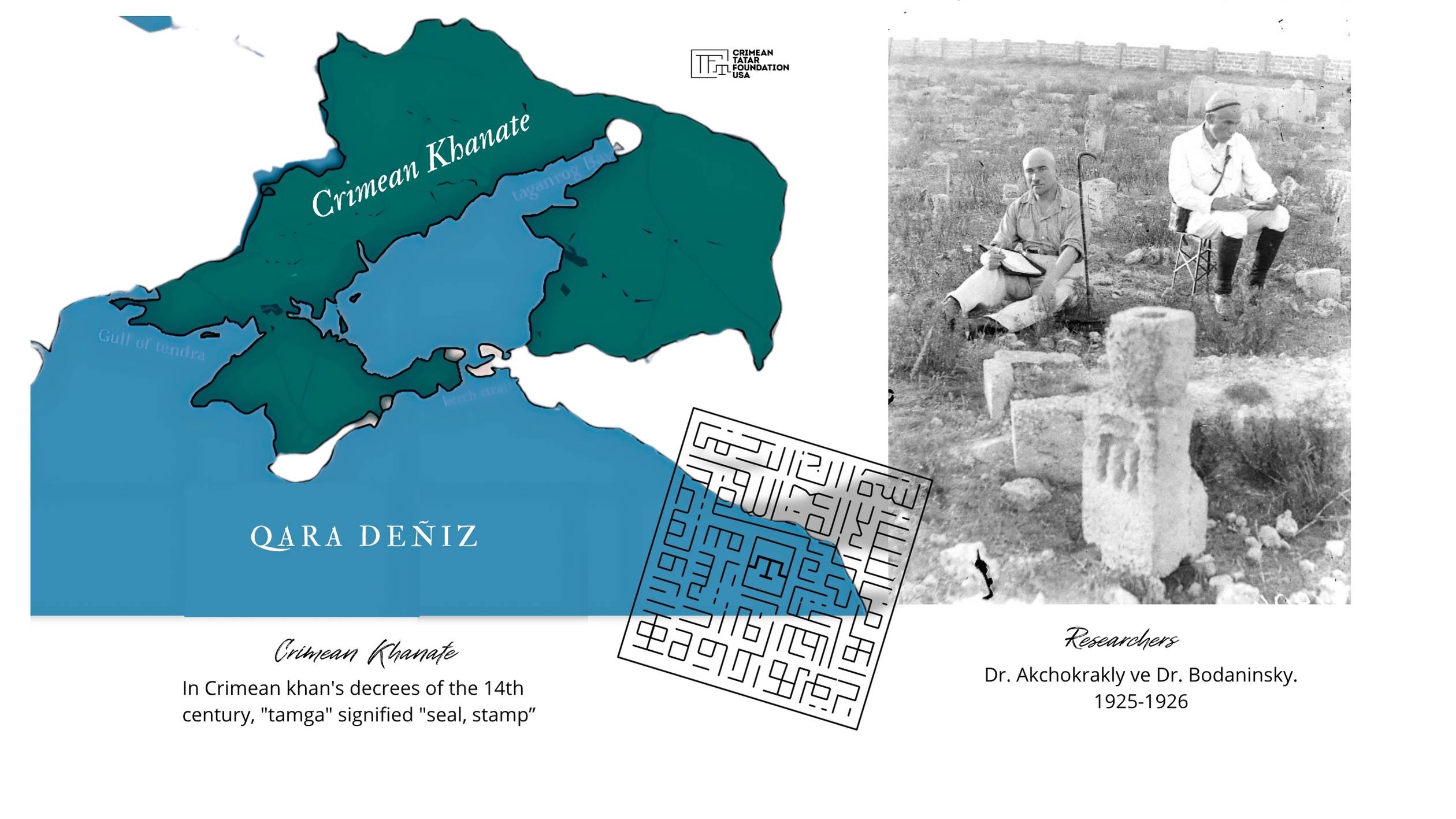

The Crimean Khanate, which ruled from 1441 to 1783, created what may have been history’s first functioning three-branch system of government. And remarkably, this medieval democracy encoded its fundamental principle directly into its national symbol – the tamga (royal seal), representing the unity of three distinct powers.

Constitution Written in Gold

The Crimean Tatar flag, adopted in 1917 but based on centuries-old tradition, bears a blue field with a golden tamga. While most observers see an abstract symbol, historians and researchers now believe this emblem represents something revolutionary: the balance between three branches of power.

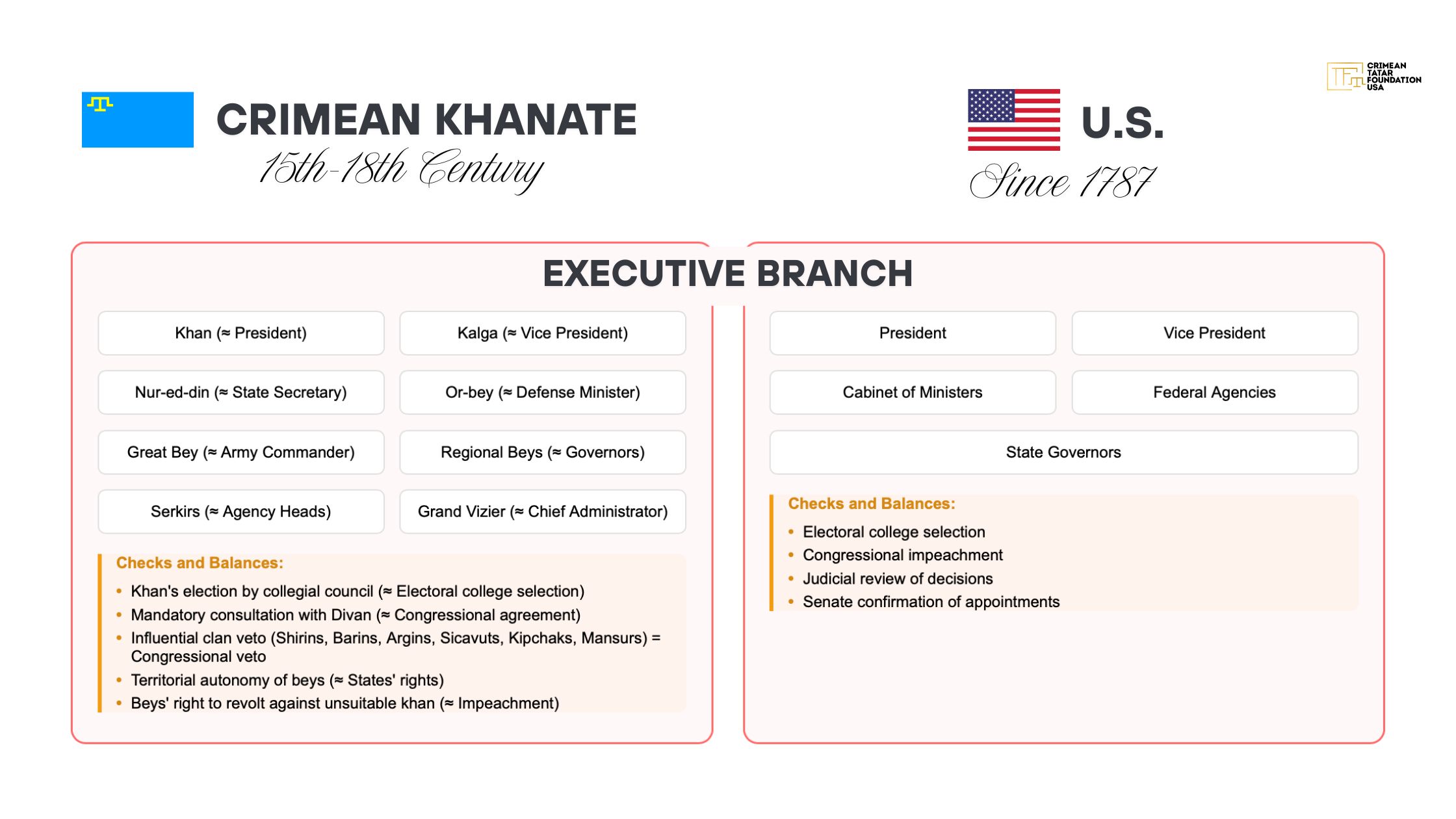

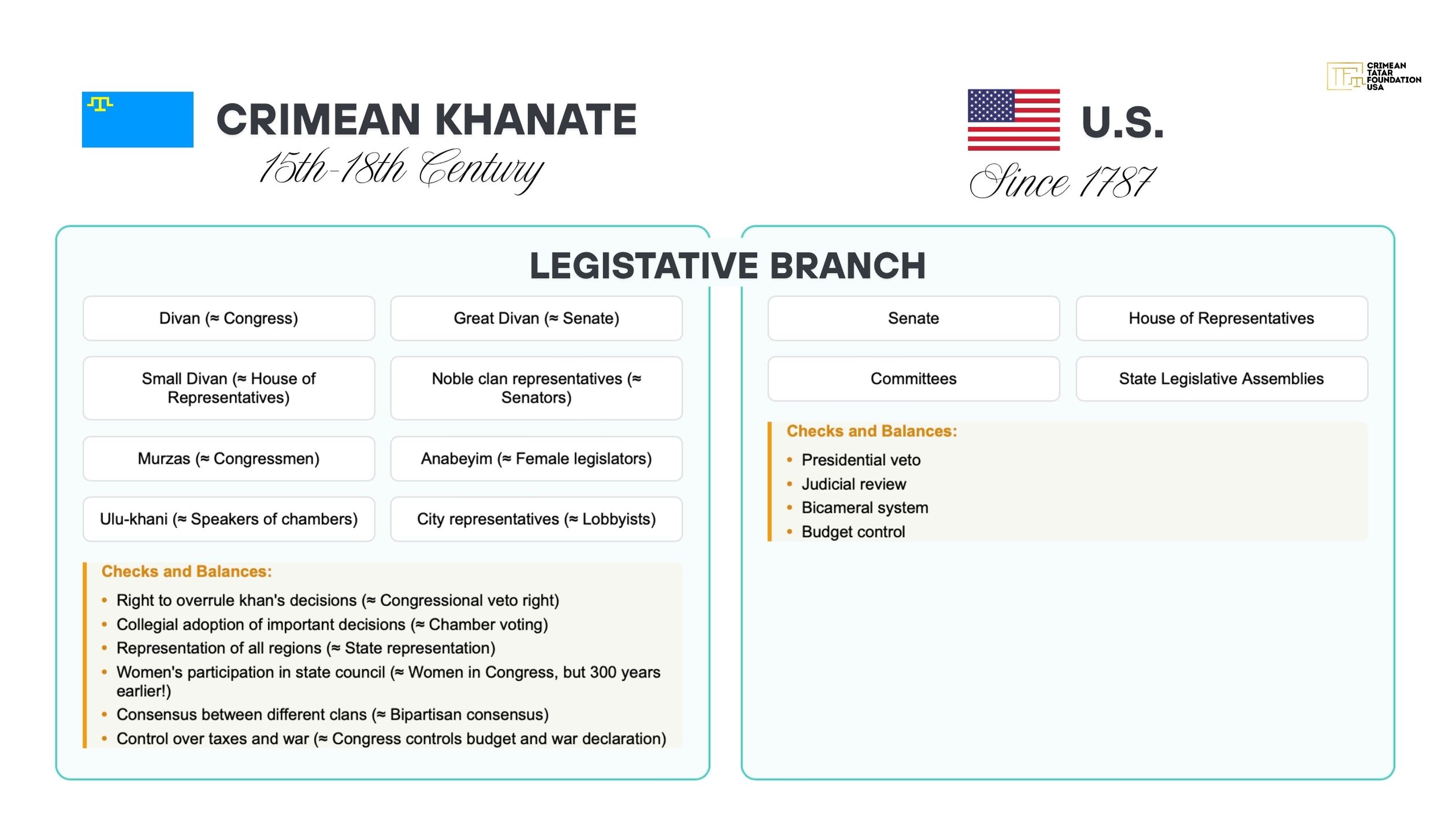

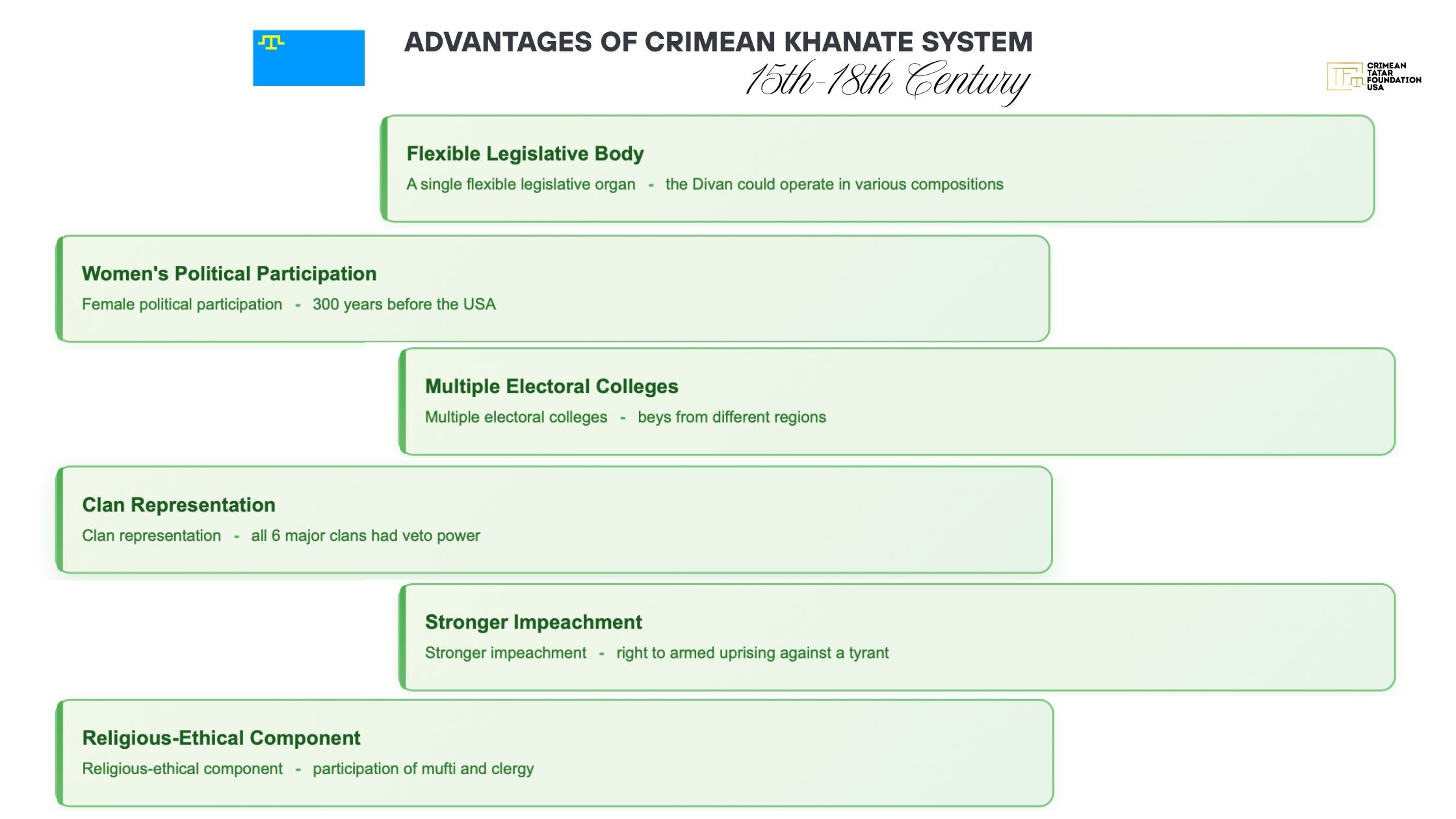

The system worked as follows: The Khan (executive power) was elected by a council of influential clan leaders – exactly as the American president is elected by an electoral college. The Divan (legislative assembly) functioned as a bicameral system: the Great Divan acted like the American Senate with representatives from each region, while the Small Divan worked as an executive council under the Khan. Remarkably, the Divan included influential women called anabeyim, who had voting rights in state decisions – 300 years before the 19th Amendment to the American Constitution.

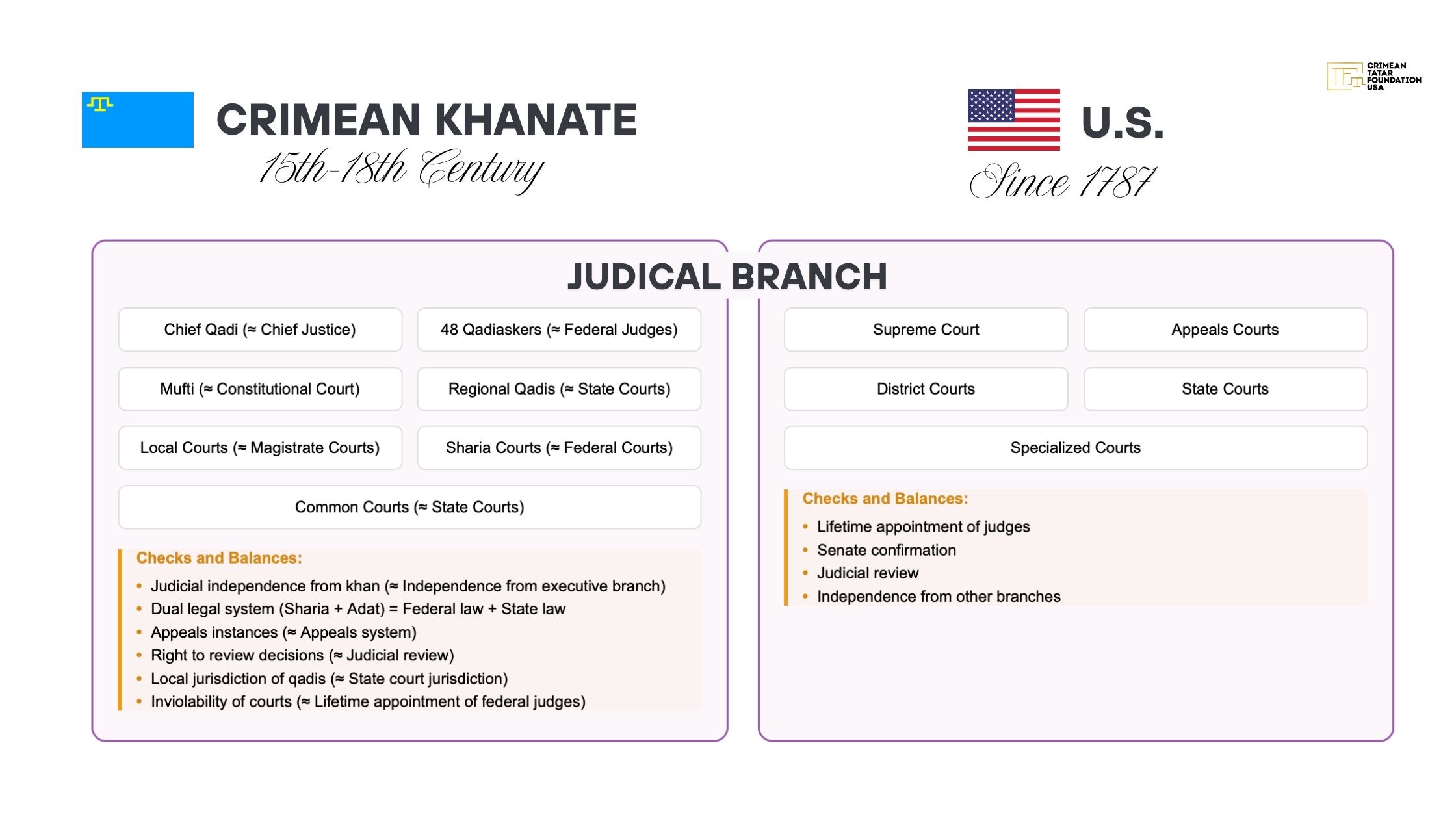

The judicial system was even more complex than the modern American one. A network of 48 independent qadis (judges) applied a dual legal system – Islamic law (Sharia) for religious matters and local customs (adat) for civil affairs. This resembles the American federal system, where both federal laws and state laws operate.

But the Crimean system was in some aspects even more democratic. While the American president can veto Congressional decisions, the Crimean Divan could completely overturn the Khan’s decisions. Six influential clans – the Shirins, Barins, Argins, Sicavuts, Kipchaks, and Mansurs – held collective veto power, creating a system of multiple checks that doesn’t exist in the American model.

An existing system of institutional checks that prevented any one person or group from accumulating absolute power. The Khan could not declare war, raise taxes, or make major appointments without consensus from the Divan.

Meritocracy in Action

This complex system of control did not emerge by accident. As historical documents show, the Crimean Tatars were able to govern a vast multiethnic state stretching from the Danube to the Volga, including not only nomadic tribes but also trading cities, agricultural regions, and various religious communities – Muslims, Christians, Orthodox, Genoese Catholics, Jews, and others.

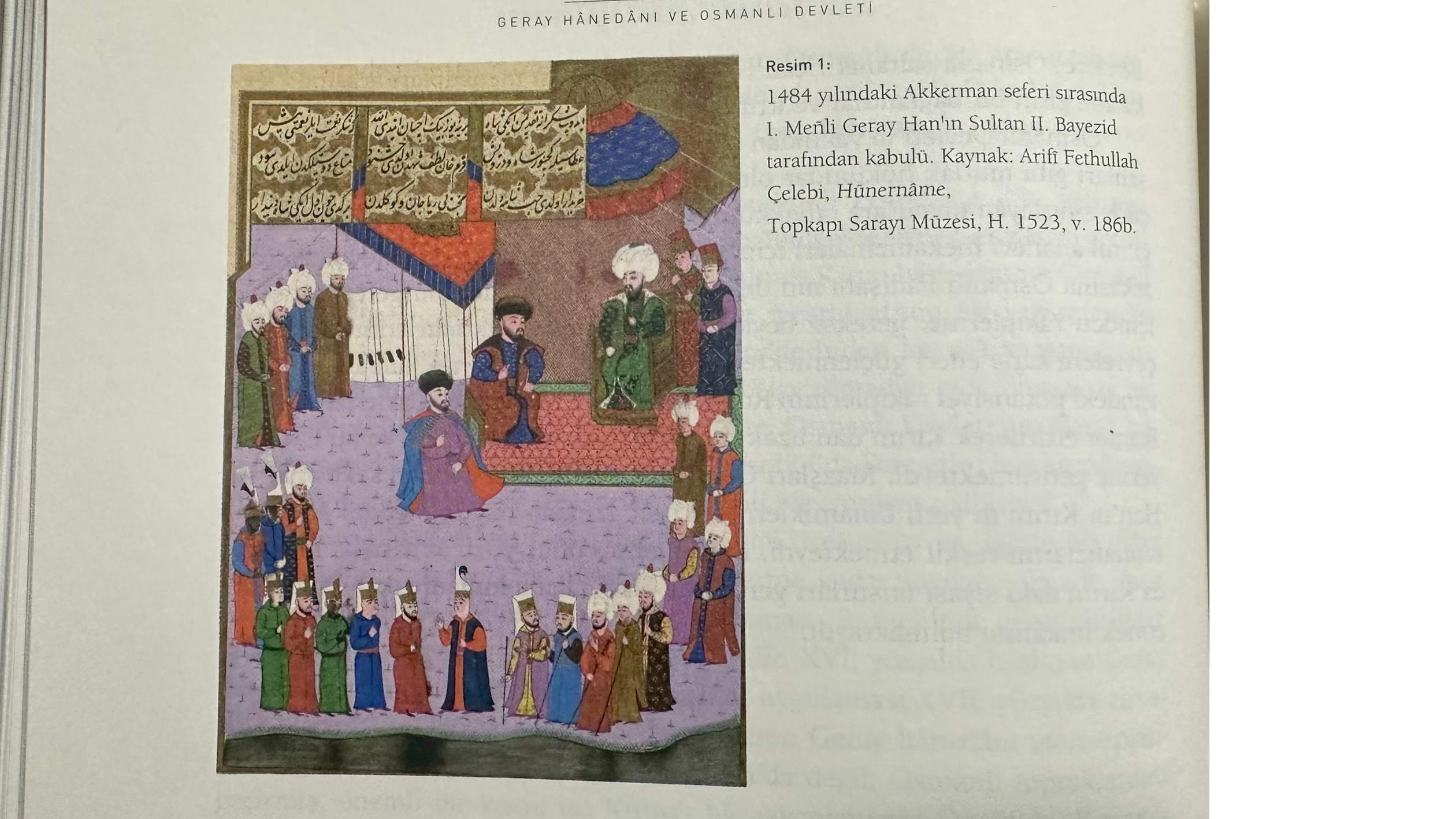

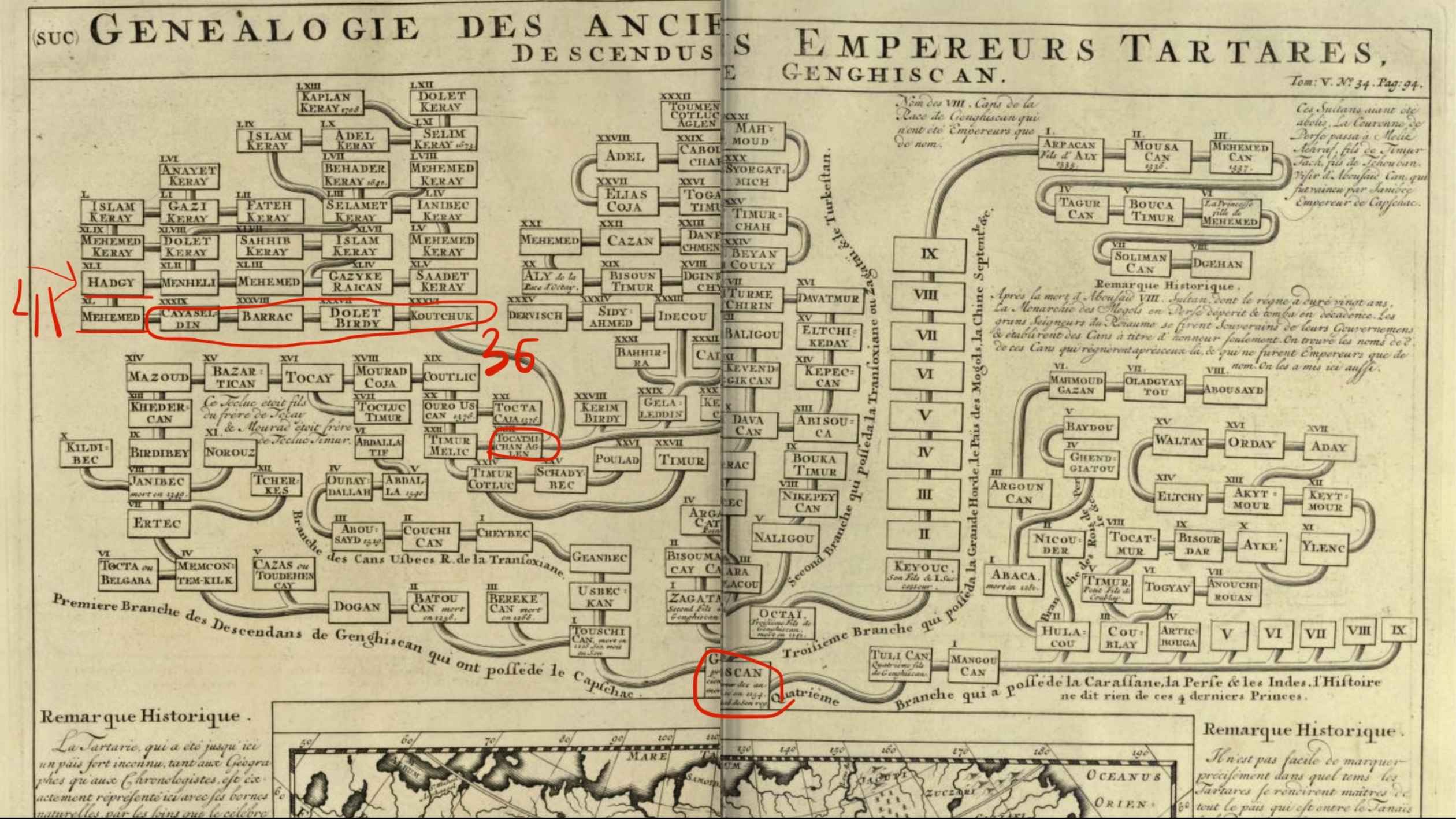

A candidate for the Khan’s throne had to prove his ability to unite these disparate forces. Dozens of princes from the Giray dynasty could claim the throne, but only one who demonstrated the following was elected: diplomatic mastery – the ability to negotiate simultaneously with the Ottoman Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Muscovite state. Military leadership – the capacity to command both nomadic cavalry and infantry, artillery in fortresses. Economic wisdom – understanding of trade routes, tax policy, monetary affairs. Inter-clan authority – support from all six influential families: Shirins, Barins, Argins, Segauts, Kipchaks, Mansurs

The system functioned as a comprehensive evaluation mechanism that ensured only the most capable leaders could ascend to power. The multi-tiered selection process required candidates to demonstrate sustained competence across multiple domains – diplomatic, military, economic, and political – before gaining the confidence of regional power centers. This institutional framework created powerful incentives for continuous performance, as maintaining legitimacy required ongoing demonstration of effective governance rather than relying solely on hereditary claims or initial appointment.

While European thrones were inherited by right of birth, often going to incapable rulers, the Crimean Tatar system ensured that power went to the most qualified candidate. The Khan was a leader who earned his position through competence and popular trust.

Direct Influence on American Founders

New archival research reveals intriguing connections between the Crimean system and American constitutional thought. Several founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, were avid readers of travel literature and political theory about Islamic systems of governance. Ottoman diplomatic documents from the 18th century show extensive correspondence with European intellectuals about Crimean administrative practices.

Jefferson owned a Quran from 1765 and studied Islamic law. His library contained over 6,000 books, including extensive materials on religion and governmental systems. Adams and Jefferson in their 1813 correspondence mention studying the works of “Frederick of Prussia, Hume, Gibbon, Bolingbroke, Rousseau, and Voltaire” as sources of ideas about government. Research confirms that the founding fathers “seem to have been inspired by the Prophet Muhammad.”

Both systems arose from similar challenges: how to balance competing interests, prevent tyranny, and maintain legitimacy among a diverse population. The Crimean Khanate governed various ethnic communities – Genoese merchants, Alans, Goths, Elinny, and others – a multicultural challenge analogous to what American founders faced when creating a union of different states.

Democracy in the Islamic World

This challenges prevailing narratives about the origins of democracy. While European monarchies were consolidating absolute power, this Muslim Crimean Tatar state was developing complex power-sharing arrangements. The Crimean system drew from Mongol administrative traditions, Islamic jurisprudential principles, and Turkic tribal governance – creating a unique hybrid that lasted more than three centuries.

The system’s longevity proves its effectiveness. Despite constant external pressure from the Ottoman Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and ultimately Russia, the Crimean Khanate’s governmental structure remained stable for more than 300 years.

Comparative Analysis: Crimea vs. America

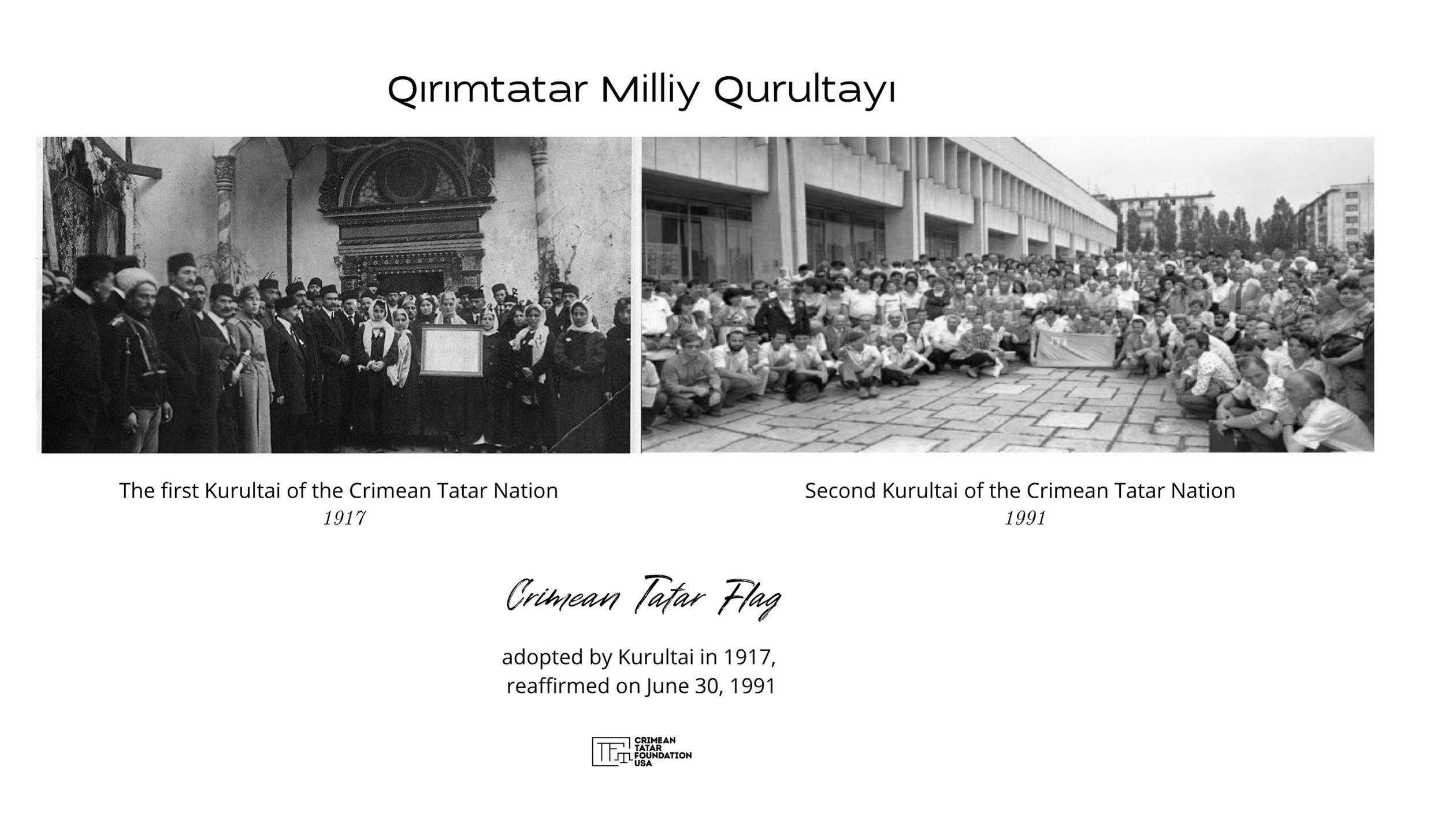

The parallels between Crimean Tatar and American systems are striking, but the Crimean model was more progressive in many aspects. When American colonists were still living under British crown rule, Crimean Tatars were already practicing a complex electoral system. In the electoral system, the Crimean Khanate of the 15th-18th centuries applied the principle where the Khan was elected by a college of beys from all regions and clans, remarkably similar to the American electoral college from states, created four centuries later. Moreover, the Crimean People’s Republic of 1917 introduced universal suffrage, including women, preceding the USA by three years.

Legislative power in the Crimean system was more inclusive from the beginning. The Divan included representatives of nobility, cities, clergy, and most notably – women, while the American Congress initially excluded women, African Americans, and Native Americans. The system of checks and balances in Crimea was also more sophisticated: six influential clans had collective veto rights, and in extreme cases – the constitutional right to remove an ineffective ruler through organized resistance, providing more reliable protection against abuse of power compared to American impeachment procedures through Congress.

Federal principles were applied by Crimean Tatars long before American founding fathers. Regional beys possessed significant autonomy in their territories, managing local affairs, tax collection, and even maintaining their own armed forces. This resembles the American concept of states’ rights, but with an even greater degree of self-governance. Judicial independence was ensured through a network of 48 independent judges applying a dual legal system – Islamic law for religious matters and local customs for civil affairs, creating a more flexible legal structure than the modern division between federal courts and state courts.

Dr. Fisher notes a particularly striking historical irony: “When American colonists fought for representation without taxation, Crimean Tatars had already been practicing the principle of ‘no taxes without Divan consent’ for three centuries.” This principle, which became a cornerstone of the American Revolution, was routine practice in the Crimean Tatar state since the 15th century.

When American revolutionaries in 1776 proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence the people’s right to “alter or abolish” government that doesn’t serve their interests, Crimean Tatars had already been applying the institutionalized right of beys to remove an ineffective Khan for five centuries. When US founders in 1787 invented federalism as a way to govern diverse states, the Crimean Khanate had already successfully governed a multiethnic state through a system of regional autonomy for three centuries.

Even more surprising are the parallels in gender equality. While American suffragettes of the 1910s demanded voting rights, citing “natural human rights,” Crimean Tatar anabeyim participated in state governance since the 15th century not as a revolutionary innovation, but as an integral part of political tradition. “American women gained suffrage in 1920 after decades of struggle. Crimean Tatars in 1917 granted it naturally, restoring centuries-old practice.

Even the principle of separation of church and state, which Americans consider one of their main achievements, had Crimean Tatar roots. The Khanate’s dual legal system – where religious matters were decided by Islamic courts and civil affairs by local customs – ensured pluralism that Americans only began to theoretically comprehend in the 18th century.

Constitution of 1917: Revival in Months

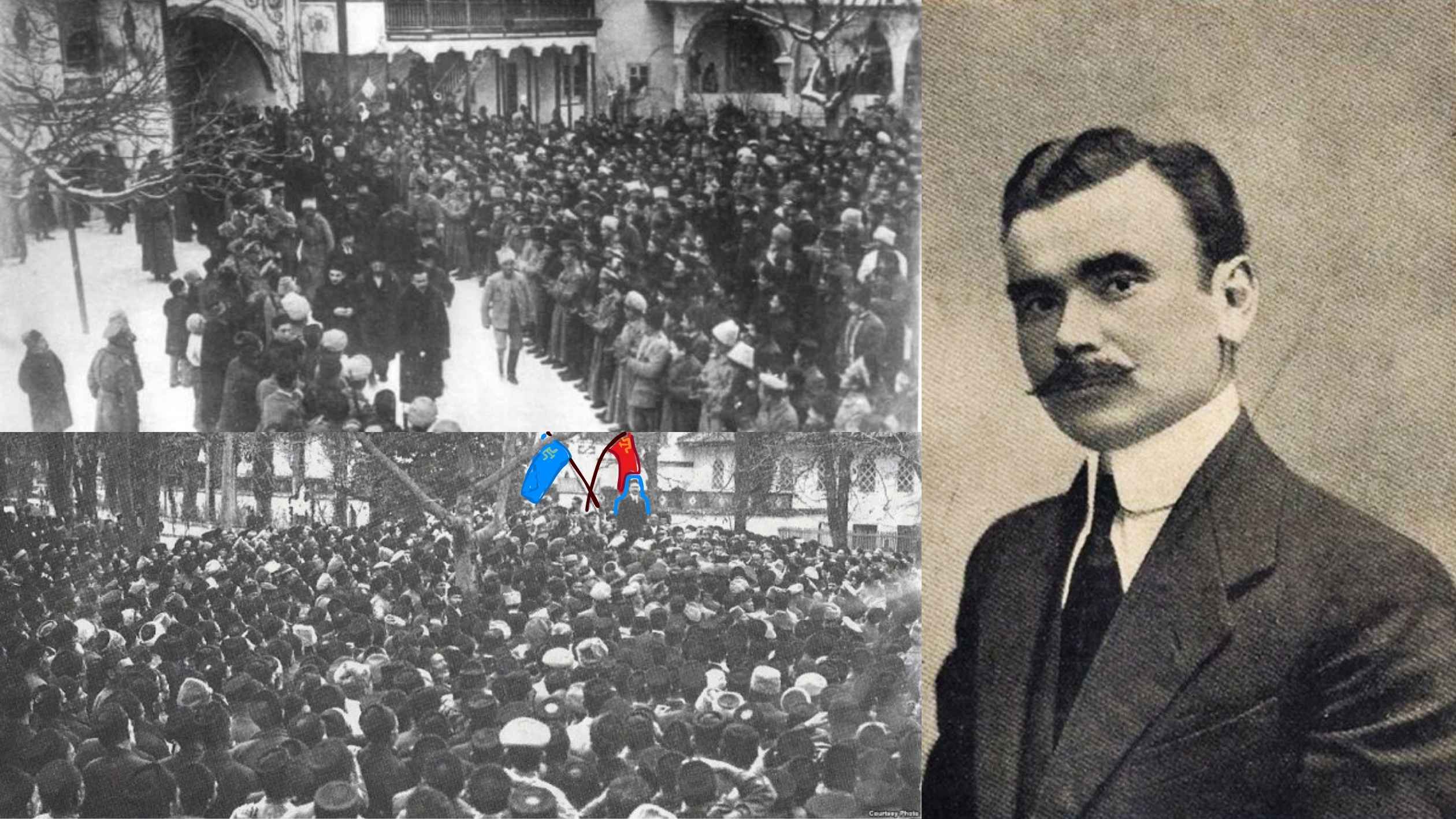

The most striking evidence of the sustainability of Crimean Tatar democratic tradition was the incredibly rapid restoration of statehood in 1917. When the Russian Empire collapsed, Crimean Tatars restored the Crimean People’s Republic in a matter of months, based on ancient Khanate principles.

On November 26, 1917, the Kurultai (National Assembly) convened in Bakhchisaray – the first democratically elected parliament of Crimean Tatars in 134 years. In an incredibly short time – just four months – they adopted a constitution based on 15th-18th century separation of powers principles, restored the three-branch system: President (analogous to Khan), Kurultai (analogous to Divan), and independent judicial system. They guaranteed equal rights to all ethnic and religious groups in Crimea, granted women suffrage – three years before the USA, established a bill of rights protecting freedom of speech, religion, and assembly.

Noman Çelebicihan, elected as the first president of the republic, formulated a vision of multinational democracy in his keynote speech before the Kurultai opening on November 28, 1917: “On the Crimean peninsula grow multicolored roses, lilies, tulips. And each of these graceful flowers has its own special beauty, its own special delicate fragrance. These roses, these flowers – are the peoples living in Crimea: Tatars, Russians, Armenians, Jews, Germans, and others. The goal of the Kurultai – bringing them together, to compose from them a beautiful and graceful bouquet, to establish on the beautiful island of Crimea a true civilized Switzerland.”

This speech reflected not only a poetic metaphor but a political program: restoration of centuries-old Crimean Tatar statehood traditions with modern democratic principles of equality for all peoples.

Tragedy of Rapid Collapse

The speed of Crimean Tatar state restoration in 1917 was matched only by the speed of its destruction. The Bolsheviks, who came to power in Russia, could not tolerate an alternative democratic model on their borders.

In January 1918, just two months after independence was proclaimed, Bolshevik forces occupied Crimea. Noman Çelebicihan was brutally murdered, parliament dissolved, constitution annulled. The democratic experiment rooted in the 15th century was destroyed within weeks.

This was not just a political revolution. The Bolsheviks understood that the Crimean Tatar model posed an existential threat to their totalitarian communist project. Here was a working example of Islamic democracy, federalism, gender equality – everything that contradicted their narrative.

The tragedy of Crimean Tatar history lies not only in the physical destruction of the nation but in the erasure of memory about these democratic traditions. The world lost a unique example of how Eastern and Western, Islamic and secular, nomadic and sedentary traditions could create a viable democratic model.

500-Year Cover-Up?

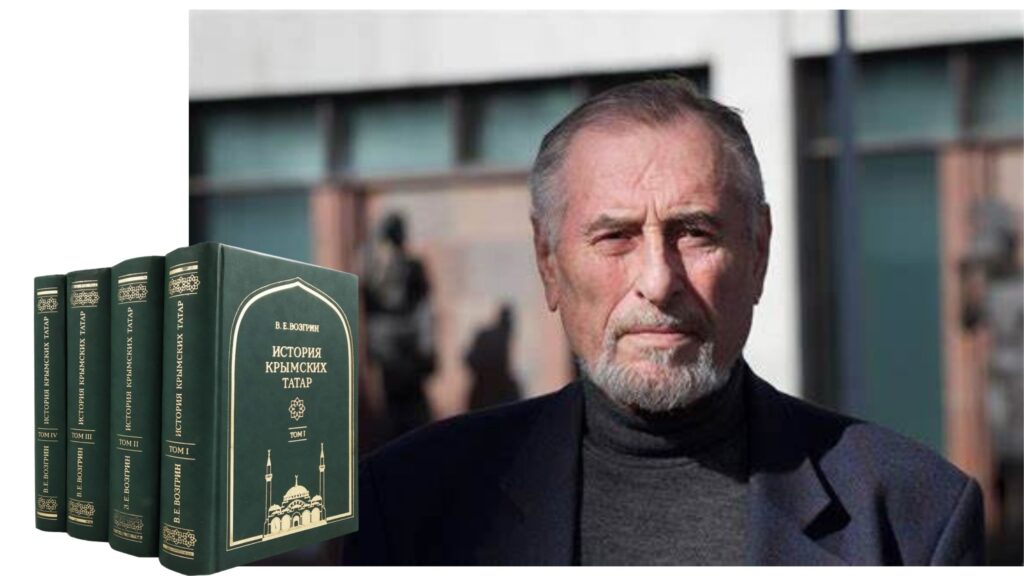

The systematic erasure of this history raises troubling questions about historical narratives and imperial ambitions. The key reason for the systematic destruction of Crimean Tatars and their heritage lies in the fact that Crimean Tatar historical memory represented a fundamental threat to Russian imperial narrative. The Crimean Khanate (1441-1783) demonstrated an alternative model of successful statehood – Islamic democracy with a developed system of separation of powers, multiethnic tolerant governance, and women’s political participation 342 years before similar institutions appeared in Europe and the USA. This “dangerous memory” not only undermined Russian myths about “civilizing mission” and “backwardness” of conquered peoples but also created legal grounds for territorial claims of Crimea’s indigenous people, questioning the legitimacy of Russian possession of the peninsula. This is precisely why every period of Crimean Tatar cultural revival – from the publication of Vozgrin’s three-volume work to the release of the film “Haytarma” in 2013 – immediately met preventive repressions, culminating in the occupation of Crimea in 2014 as an attempt to finally erase the living alternative to the Russian imperial project.

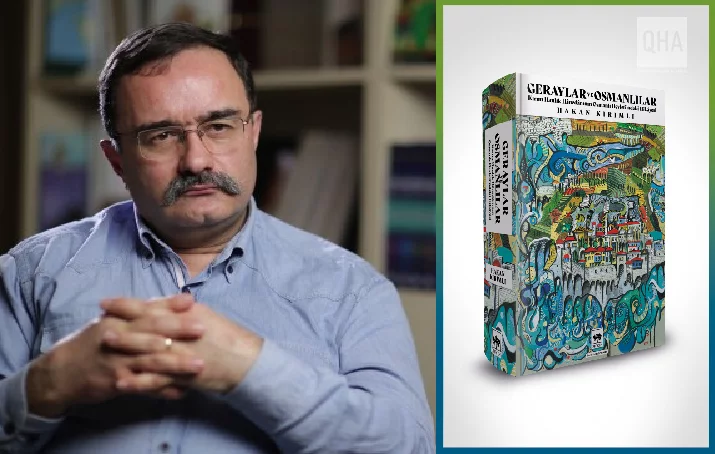

“There was a deliberate attempt to erase this history,” argues Dr. Hakan Kirimli, Director of the Center for Russian Studies at Bilkent University and author of the definitive works on Crimean Tatar history. “A Muslim state that developed democratic principles before Europe? That didn’t fit anyone’s narrative.”

But even after the USSR’s collapse, Russian academic scholarship did not revise these assessments. On the contrary, as analysis of textbooks and scholarly publications from the past thirty years shows, the silencing of Crimean Tatar achievements has become even more targeted. Ignored are not only the Khanate’s political innovations, but also its contributions to international trade, diplomacy, architecture, and jurisprudence – achievements that allowed this state to flourish for more than three centuries under constant geopolitical pressure.

Linguistic evidence is no less compelling. The word “customs” in modern Russian derives from the Turkic tamga, originally meaning “seal” or “official mark.” Even more surprisingly, some etymologists now trace the word “money” (den’gi) to the same Turkic root (tenge), highlighting the khanate’s influence on international commerce and law.

Interrupted Legacy

Stalin’s 1944 genocide of the entire Crimean Tatar nation seemed to forever end their political history. Their flag was banned under penalty of death, their national identity systematically erased.

But symbols endure. When Crimean Tatars began returning to their homeland in the 1990s, they again adopted their ancient flag. Today this blue banner with golden tamga flies at political rallies, cultural events, and memorial services around the world – a reminder of democratic values and traditions that predate most European parliaments.

Contemporary Struggle

Today, as Russia continues genocidal policies in Crimea and Crimean Tatars face renewed persecution under Russian occupation since 2014, the tamga has acquired new meaning. Moscow, as under the Empire and Soviets, has banned the symbol, declaring it “Ukrainianist,” while forcing Crimean Tatar children to study Russian versions of their history that omit the Khanate’s democratic legacy.

The European Union has recognized the tamga as a symbol of indigenous rights, while Ukraine has included Crimean Tatar symbols alongside the Ukrainian flag in official ceremonies – a gesture that speaks to broader questions of cultural and political preservation and historical justice.

Human rights organizations document ongoing persecution: Crimean Tatar activists face imprisonment, their schools are closed, their language marginalized. The Mejlis, their traditional representative assembly, was banned as a “terrorist organization.” This is a pattern that repeats the systematic erasure undertaken by previous Russian regimes.

This struggle reflects a larger geopolitical pattern that extends far beyond Crimea. Ukraine’s post-2014 trajectory toward European democratic institutions represents a fundamental challenge to Russia’s sphere of influence – a challenge that Moscow has met with increasingly authoritarian measures. From the perspective of democratic consolidation theory, Ukraine’s integration with EU structures and NATO partnerships signals a decisive break from post-Soviet clientelism toward pluralistic governance.

Russia’s response – annexing Crimea, supporting separatist movements, and ultimately launching a full-scale invasion in 2022 – follows classic patterns of imperial resistance to peripheral democratization. The Kremlin’s systematic suppression of Crimean Tatar institutions parallels its broader strategy of eliminating alternative centers of legitimacy that challenge its hegemonic narrative. For Putin’s regime, the very existence of a successful democratic Ukraine poses an existential threat to its authoritarian model, demonstrating to Russian citizens that post-Soviet societies can indeed achieve European standards of governance and prosperity without a paternalistic system of Kremlin control.

Unanswered Questions

Significant gaps remain in the historical record. Russian archives from the 18th and 19th centuries remain largely inaccessible to independent researchers. Chinese sources from the Mongol period may contain additional information. Archaeological work in Crimea has been suspended since 2014, and even before that, Crimean Tatar scholars faced obstacles in leading expeditions or participating in excavations.

Crimean Tatar researchers work with fragments, but even these fragments tell an extraordinary story.

Recent discoveries have only deepened the mystery. Ottoman archives in Istanbul contain detailed reports on Crimean governmental procedures. Venetian trading accounts describe the Khanate’s legal system in remarkable detail. Polish and Lithuanian diplomatic records reveal complex treaty negotiations that suggest comprehensive governmental structures.

Lessons for Today

As democracies worldwide face unprecedented challenges, the Crimean Tatar experience offers both inspiration and warning. Their system successfully balanced competing forces for centuries, survived foreign domination, and maintained legitimacy across ethnic and religious lines.

But it also shows democracy’s fragility. Complex governmental systems can disappear in a short time when faced with imperial ambitions or totalitarian communist ideology.

The comparison of the Crimean Khanate with the USA shows that democracy is not a European invention, but a universal human need that found expression in the most diverse cultures and epochs. The Crimean Tatar model was no less sophisticated and in many ways more progressive than its American counterpart. Restoring this historical memory is not just a matter of justice, but an opportunity to enrich our understanding of humanity’s democratic possibilities.

Symbol for the Future

The tamga – this small golden symbol – continues to inspire those who see in it not just a relic of the past, but a blueprint for the future. In an era when democracy itself faces new challenges, perhaps it’s time to remember that its roots run deeper and wider than we often assume.

The principles that inspired Independence Hall in 1787 were already being practiced in the palaces of Bakhchisaray three centuries earlier. Crimean Tatars invented separation of powers not as a theoretical exercise, but as a practical solution for governing a diverse, dynamic society.

Their example reminds us that democracy is not the prerogative of any one culture or epoch – it is a human universal, waiting to be discovered wherever people gather to solve the eternal challenge of living together in freedom.

Dr. Zera Mustafaieva M.A., and Dr. Zarema Mustafaieva M.A., are Research Directors at the Crimean Tatar Foundation USA Inc. and graduate researchers at Purdue University’s Brian Lamb School of Communication. Their research examines the intersection of Crimean Tatar political history and contemporary geopolitical developments.

This investigation was supported by Purdue University and included archival research in Kyiv, Simferopol, Bakhchisaray, New York, and Washington D.C.

Related Reading

📖 No Right to Exchange: How Crimean Tatar Soldiers Became Hostages to Their Identity in Russian CaptivityAn investigation into the systematic targeting of Crimean Tatar POWs and the international law violations in their treatment

📖 Musa Mamut: How Ignored Genocide Became Putin’s War Blueprint How the 1944 deportation provided the template for Russia’s contemporary genocidal policies

📖 The Legal Barriers to Trump’s Ukraine Peace Plan: A Focus on Crimea Why international law makes any peace deal excluding Crimean Tatar rights legally impossible

Further Reading

Essential Primary Sources:

Academic Studies:

Kirimli, Hakan. National Movements and National Identity among the Crimean Tatars (1905-1916). Brill, 1996.

Uehling, Greta Lynn. Beyond Memory: The Crimean Tatars’ Deportation and Return. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Mustafaieva, Zera. Structural Violence Against the Crimean Tatar People in 1921-1923

Contemporary Analysis:

Digital Archives and Resources:

Documentary Films:

For those interested in comparative constitutional history:

Madison, James. The Federalist Papers. 1787-1788.

Montesquieu, Charles de. The Spirit of Laws. 1748.

Ibn Khaldun. The Muqaddimah. 1377.

Al-Mawardi. The Ordinances of Government. 1045.